Kristina Hill, Affil. ASLA

on Climate Change

At a recent conference on designing wildlife habitats, you said cities are always warmer than surrounding areas because of the urban heat island effect. Cities are then precursors to climate change. In fact, “cities are at the edge of climate change.” What can cities’ experience with elevated heat levels teach us about best and worst ways to mitigate and adapt to climate change?

The fact is, I have yet to see any “worst” – except perhaps no preparation at all! Here, in the U.S., we live in what I call the American Media Bubble – where the media aren’t using climate change to sell papers, unlike their Canadian and European counterparts. Since they don’t see the headlines the rest of the world is reading, the average American doesn’t know what’s at stake. And as a result, their elected officials are discouraged from taking action. But the rest of the world is starting to prepare. Our economic future, and the health, safety and welfare of many of our citizens, depends on learning from the best practices that are out there.

I’ll say something about the best instead. The best approach I know of can be simply described using three categories of actions: to protect, renew, and re-tool. That means, to protect the most vulnerable people and places, especially the ones that offer the greatest future diversity and flexibility; to renew our basic resources, like soil fertility, water quality and quantity, air quality, and human health; and to re-tool, altering urban systems – buildings, transit, landscapes -- to use less energy (since energy use is still a proxy for CO2 generation, unless you use only clean sources), and generate fewer wastes that can’t be used by someone else, locally. I’ll give some examples, since all three categories of action require spatial strategies and create significant roles for landscape architects who have the drive to change cities. Most American cities are just at the point of taking stock of the magnitude of their exposure to climate change, but European cities have acted and offer practical lessons learned.

Cities are at the edge of climate change in several ways. First, in the sense that enough people’s lives and property are at stake to force them to take actions to adapt. Rotterdam is investing to try to make itself “climate proof” because its Europe’s biggest cargo port city, it houses an increasingly large portion of the Dutch population, and the Dutch believe in their ability to live with the changing dynamics of water. Not only do they believe in it at home, they also see it as a major export—knowledge and ability they can share with cities all over the world, for a profit. London has built one of the world’s most famous storm barriers on the Thames because the land in the center of the city is so valuable, and the population so large, that they can’t afford NOT to protect it. Hamburg has used a different strategy – also driven by the location of its cargo port inside the city limits. It will allow flooding, but designed a major new part of the city to be resilient to high water, with water-proof parking garages, a network of emergency pedestrian walkways 20 feet above the street, and no residential units at ground level. Even the parks in this new Harbor City district are designed to withstand battering by waves and storm surge, either by floating as the waters rise, or by incorporating lots of hard surfaces that only need to be washed off when the waters recede.

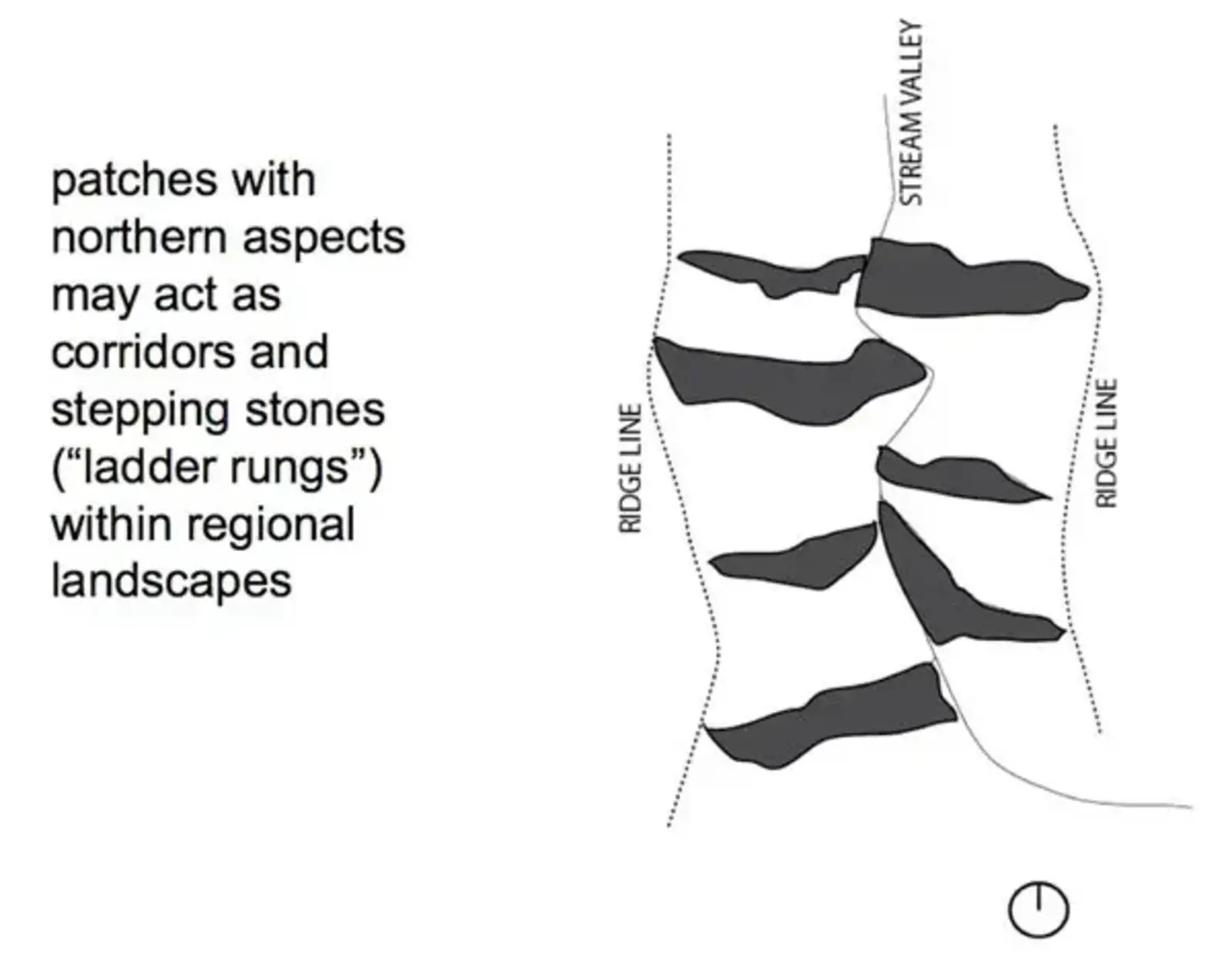

These examples fall into the “protect” category of adaptive actions. So would efforts to conserve north-facing slopes, where many of today’s native plant species may persist the longest as summer heat waves and droughts become more extreme, more common, and of greater duration. North-facing slopes might be our Noah’s Ark, bringing species with us into the future and buying them time to adapt – behaviorally or genetically -- if they are able.

But from an ethical point of view, the most important way to protect cities is to protect the most vulnerable people who live in them: low-income children and their caregivers (often single mothers), people with illnesses, and seniors. All over the world, people with even modest wealth will be able to protect themselves. They’ll buy better air conditioning, pay more for electricity as fuel prices rise, stay in a hotel when floods come, get health care when they need it, maybe even relocate by buying a home in a less vulnerable location. Children born into poor families where their mothers have to both work and care for them without paid help are in a very different situation. Many people in New Orleans who lived paycheck to paycheck did not evacuate when Katrina came, not because they were stubborn or unaware but because it was the end of the month and they couldn’t afford to stay in a motel. Or didn’t own a car to evacuate with in the first place. Most people in the world are that poor. If we want to adapt, we need to help them adapt. Those children contain the seeds of our future creativity. Adapting cities without protecting children is not only unethical, it’s unwise.

New York City, London, and other major cities have been creating detailed climate change adaptation action plans. In your mind, what do cities need to focus on the most as they develop these plans? What about smaller communities creating plans with very limited resources?

This question offers me a chance to provide examples of both the renewal and the re-tooling actions.

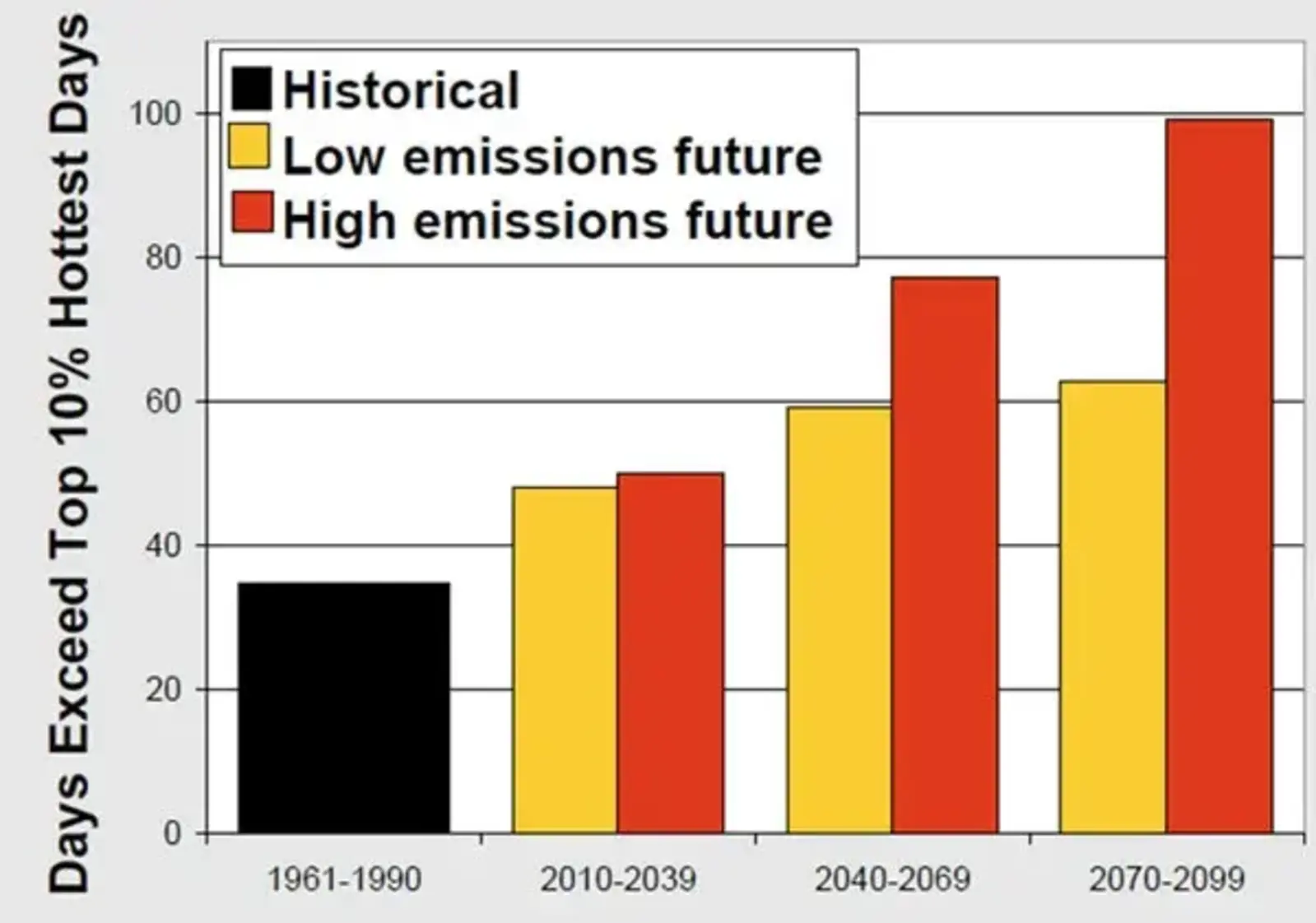

In the U.S., Chicago has the most detailed and strategic climate adaptation plan. Mayor Daly made the environment one of his priorities, and he and his staff have done their best work in this area. Even so, what they mostly have is a good sense of what the problems are -- but not a lot of solutions. This is principally because the problems will emerge over time, and it’s difficult in our political climate to spend lots of public money before a problem is part of everyday life. This past year was a case in point – in winter, there were unusually large snowstorms in cities like Washington, D.C., and people claimed that “global warming” was a hoax. By summer, we found ourselves on track to experience the hottest year ever across the planet as a whole. The second-hottest year was 2005. People have a hard time understanding that the real problem is not a gradual warming trend; the real problem is that we’re facing an increase in climate extremes – from snowfall to heat and from floods to drought. Flooding this year in Brazil and now Pakistan has affected the health and security of millions of people, most of whom are children. Cities need to recognize that it’s not about planning for an average of 2-10 degrees warmer summers; it’s the new extremes in rainfall, flooding, drought, and the duration of heat waves that will really challenge our infrastructure and affect our lives. Cities need to focus on these extremes, and make investments to be more resilient to them in terms of both the duration and the magnitude of these extreme circumstances.

That’s what I mean by “re-tooling.” Urban systems represent enormous investments of public money, and once built, the debt accrued by building them creates a long lag time before these expensive systems can be changed significantly. Landscape architects need to wade into some of the policy and planning debates that surround these investments of public money. If we were designing a house and landscape for ourselves and everyone we care about to live in, together, 30 years from now, we wouldn’t design it based on our income and needs today. When cities build infrastructure, or develop/re-develop large areas of land, those projects are meant to have value and perform as intended for at least 30 years; many are intended to function for 50 or 70 years, perhaps longer. We need to question whether these urban places and systems are really being designed to perform as intended during an era of increasing climate extremes, because we and almost everyone we care about will live in them, all over the world. We need to demand investment strategies that link future debt to future performance. No project should be allowed to generate public debt for 30-40 years if it won’t add to our future capacity to adapt; if it doesn’t increase our resilience, it should be paid for only out of today’s money, or not be built at all.

Taking out highways makes some sense, financially as well as in terms of new land use options, because maintaining an underutilized, polluting roadway ad infinitum is expensive. The effort in the South Bronx to remove the Sheridan Expressway is a good example; it could be replaced with a mix of public and market-rate housing, and parks that increase the resilience of that district to flooding while providing clean places to swim when it’s hot. Other cities, from Portland to San Francisco and Milwaukee to Providence, have taken out highways. That kind of capital investment is expensive in the short term, but may save public money in the relatively near future while increasing resilience. Our ways of thinking about public infrastructure have to change pretty radically from the old “more is better” attitude if we want cities to avoid spending themselves into a dead-end, with lower quality of life and reduced economic competitiveness.

Cities need to focus on resilience as they make their debt commitments. If they are investing in projects that replace old highways with new ones, but don’t add significant alternatives to driving (like public transit), they’re making a mistake. Those cities will be paying for that non-adaptive project for so long, they won’t have any money to spend on adaptation. On the other hand, projects like public transit inside growing cities should be able to extend their debt over a longer period, making them more affordable, because they will expand the options of people who live in the future. They are an investment in future flexibility, and increase our adaptability to trends like rising fuel prices. That makes them an investment in resilience. Designers, public advocacy groups, elected officials, federal agencies, and bond rating agencies should use criteria like this to demand smarter decision-making with respect to climate change, and alter the type of work designers have to do in cities. No more short-term, single-purpose infrastructure (or public space or urban district plans, which are seen as more a part of infrastructure today than they have been for 150 years).

I think big cities will have to incorporate both centralized and decentralized infrastructure into their investments. Small communities, on the other hand, will likely have to choose between encouraging density or enabling more people to live off the grid in an affordable, healthy way. With greater density, we can use centralized systems to make these small cities more livable (with less driving, more walkable neighborhoods, more affordable infrastructure services). With greater energy, water and waste independence on a house by house basis, and access to cleaner transportation technologies (electric cars), small cities can provide fewer services and make themselves more resilient by keeping their costs from growing. The latter strategy is pretty optimistic that cleaner, house-based technologies will be ready and affordable, and that people will be willing to live within the limits they generate. I’m not such a technological optimist, so I’d advocate for the density strategy.

Youngstown, Ohio offers an example of the “renewal” category of actions for smaller cities. By that, I mean renewal of basic resources like soil fertility, water and air quality, health, and food security. As I understand the story that came through the media, the elected officials decided to acquire derelict residential properties using a spatial strategy that, when the houses were demolished, created a park system that would allow higher quality of life for future residents. The vegetation and water resources of the park system could be “grown” slowly over time, using successional strategies for the plants (with limited maintenance interventions) and using biological processes to help clean soils and water. Small communities that take the long view, using a 50-year timeframe to compare alternatives and focusing on their quality of life in a healthier environment, will be attractive places to live in a geographically-flexible future economy. If the land acquisition is planned well, and short-term uses are allowed that fit today’s needs – say, local food production, or even ATV recreation if it supports a disturbance regime that helps plant succession -- that same future-oriented green infrastructure can get a mayor re-elected in the short term as well.

Climate change is expected to cause mass migrations of animal and plant species. You said it’s more efficient for species escaping rising heat levels to move up in elevation as opposed to moving north. Unfortunately, for many species, there isn’t higher elevation. What design solutions can aid migration?

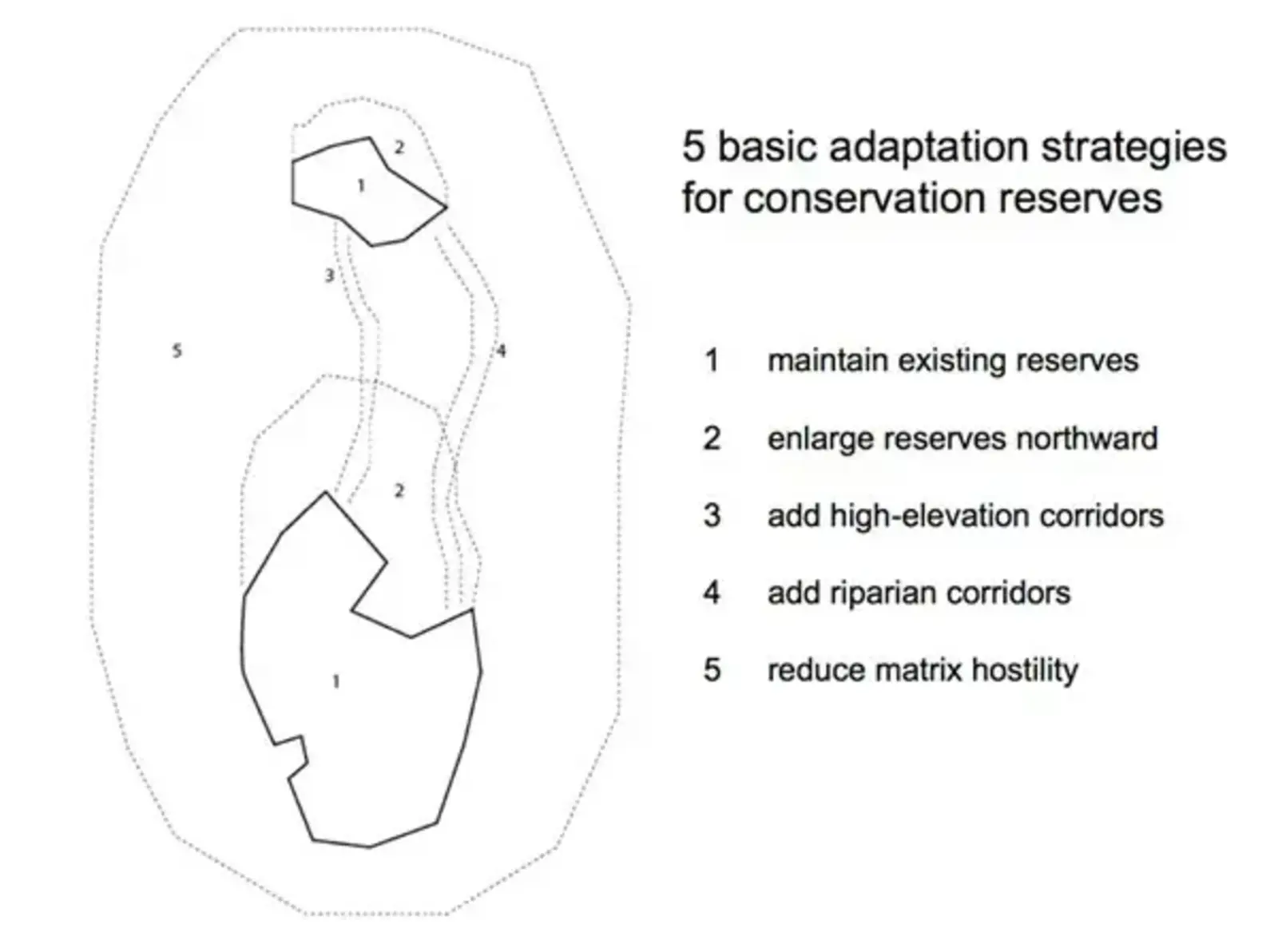

The most important planning and design strategies for biodiversity involve first protecting the land that has been conserved to date, in two ways. Number one, by adding buffer zones to their edges in which development is restricted or prevented. This is especially important on northern-aspect slopes, where characteristic regional species are more likely to persist in an era of increasing dryness and temperature extremes. Second, educating the public about the importance of reducing the negative impacts of what landscape ecologists call “the matrix” – which includes all the developed landscapes outside the reserves. This is a strategy ecologists sometimes call “reducing matrix hostility.” It basically means that even developed landscapes can contribute to the overall ability of a region to support sensitive species that lived there before development occurred. When each developed parcel manages the quality and quantity of its stormwater runoff, for example, it contributes to a healthier landscape with sustained regional biodiversity. If parcels contain fertile soils and plants that support native insects, and even allow some standing dead trees in the mix, they’re more likely to support “stop-over” feeding or perching by native birds. Improving air quality can make it possible for insects to locate and pollinate plants in developed landscapes. Reducing noise on roadways can benefit frogs that use sound in mating behavior in wetlands nearby. Building wildlife over- and under-passes can allow animals to migrate and disperse through heavily developed landscapes.

In addition to making sure the conserved patches are shored up with buffers and a region has reduced its “matrix hostility,” climate change creates an imperative to add corridors and stepping stones – both north-south (connecting across latitudes) and up-down (connecting across elevation gradients) – at all spatial scales. As the ecologist Stuart Pimm has pointed out in a recent article, it’s more efficient for species to move a few thousand feet laterally to move up by hundreds of feet of elevation as a way of staying cooler than it is to move tens or hundreds of miles north to get the same benefit. But going up in elevation is like walking the plank, because it means there is less area available as the species go up – and the solution is limited by the maximum height of the hills or mountains available.

.webp?language=en-US)