Community Catalyst: Building A Network of Public Spaces for Sanitation and Social Inclusion in Winneba, Ghana

Honor Award

Urban Design

Xinhui Chen

Faculty Advisors: Guoping Huang

University of Virginia

Complex social structures and inadequate infrastructure meet in Winneba, Ghana, where this group proposes a shade-giving, water-producing, waste-treating piece of sanitation infrastructure loosely based on local sacred groves. A pilot project initiates a biogas toilet system that converts waste to energy, allowing for on-site water purification and distribution; and fertilizer, feeding communal mango trees that provide both fruit and shade. Freeing women in the community from the burden of gathering water from farther afield, the project—built by residents, and expandable to adjacent neighborhoods over time—melds ecological benefit with social equity.

- 2020 Awards Jury

Project Credits

The Effutu Municipal Assembly

The University of Education, Winneba

Lagoon Forester, Ghana Wildlife Division of Forestry Commission

Andrews Agyekumhene

City Planner and Chair of the Winneba-Charlottesville Sister City Commission

Joe Baami

Instructor

Nancy Takahashi

Project Statement

Winneba, just like other coastal cities in West Africa, is suffering from enormous social and ecological challenges, such as inadequate infrastructure, water sanitation, food insecurity, environmental degradation, and social conflicts. This project initiates from understanding the socio-ecological role of Ghanaian public space. Research into community power in conservation, in particular, that of sacred groves, reveals its unique role in legitimizing social arrangements, addressing a sense of belonging, and reconcile differences. The success in maintaining these small eco-systems through local efforts can inform better policy-making.

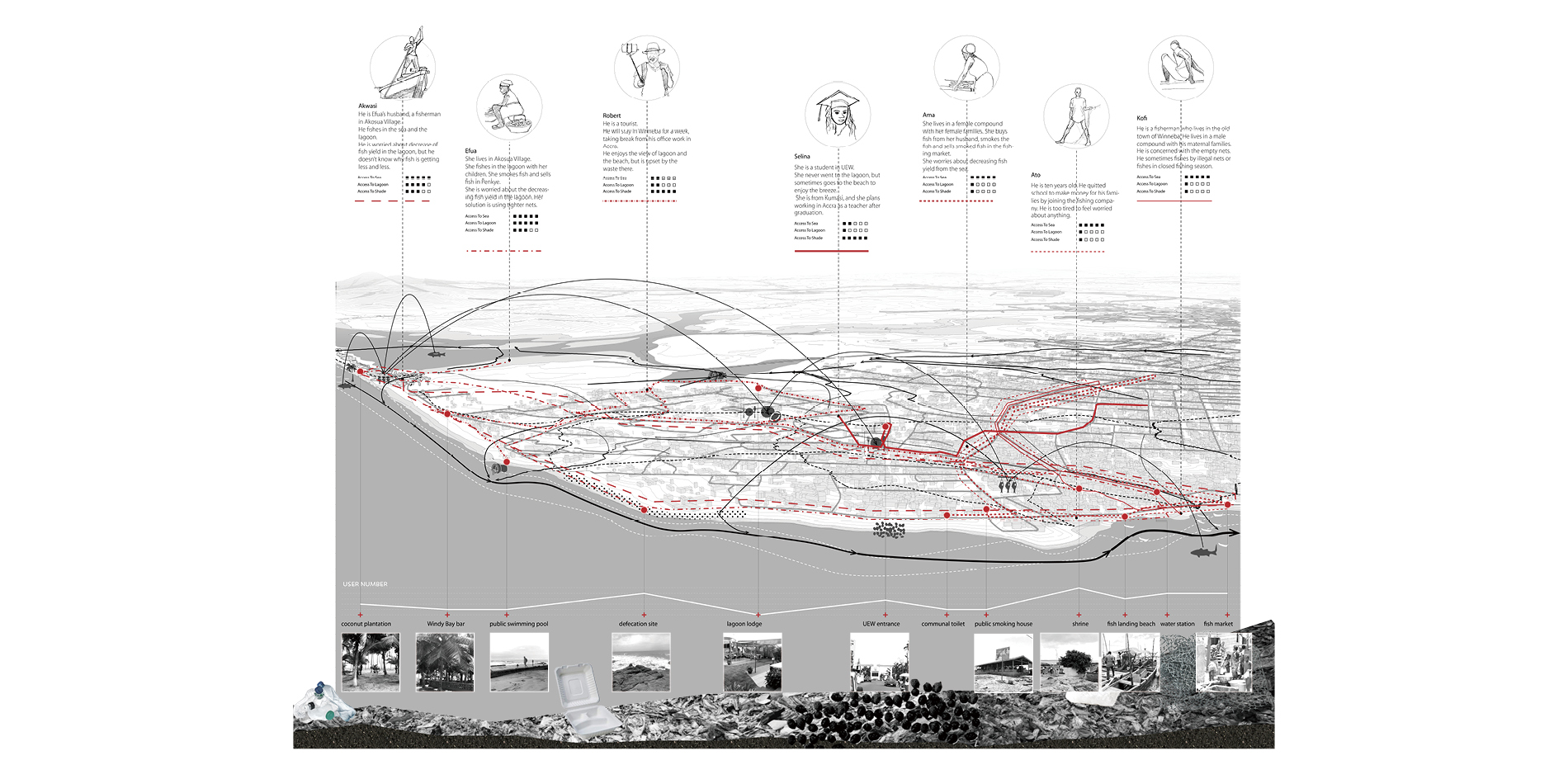

Drawing inspiration from social research and local traditions, this project proposes a network of vegetated public spaces that function as a catalyst to initiate ecological and social transformation. It encourages bottom-up community participation in each of the three phases. In addition to amenities that enable access to tree shade, clean water, public toilets, bio-energy, and food, these spaces provide a connection among residents regardless of their origin and social status. Through collaborative efforts, people of different social groups are brought together to improve social, economic, and environmental well-being.

Project Narrative

“You cannot protect the environment unless you empower people, you inform them, and you help them understand that these resources are their own, that they must protect them.”

-Wangari Maathai, Kenyan political activist and Nobel Peace Prize laureate

Context investigation

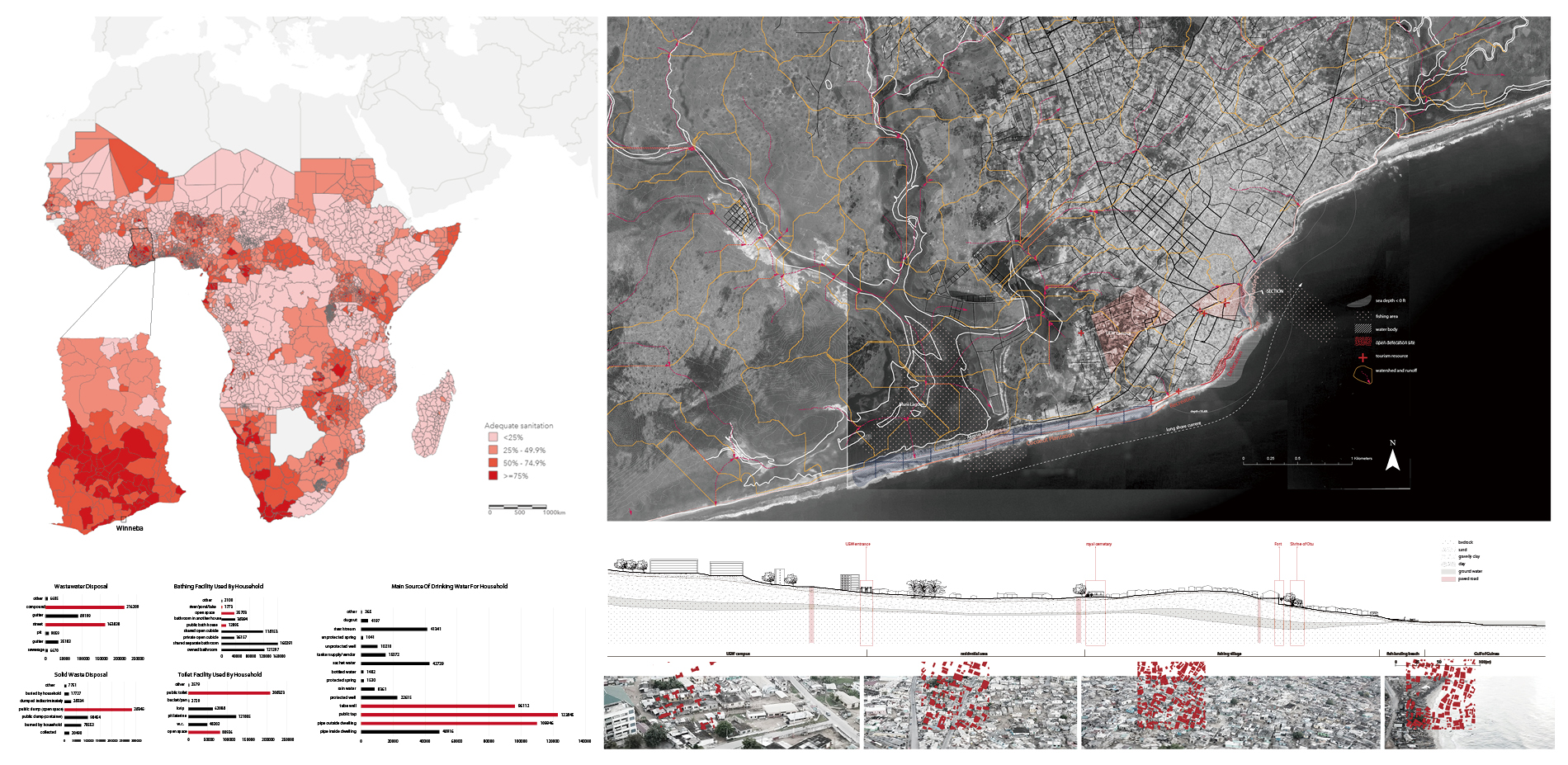

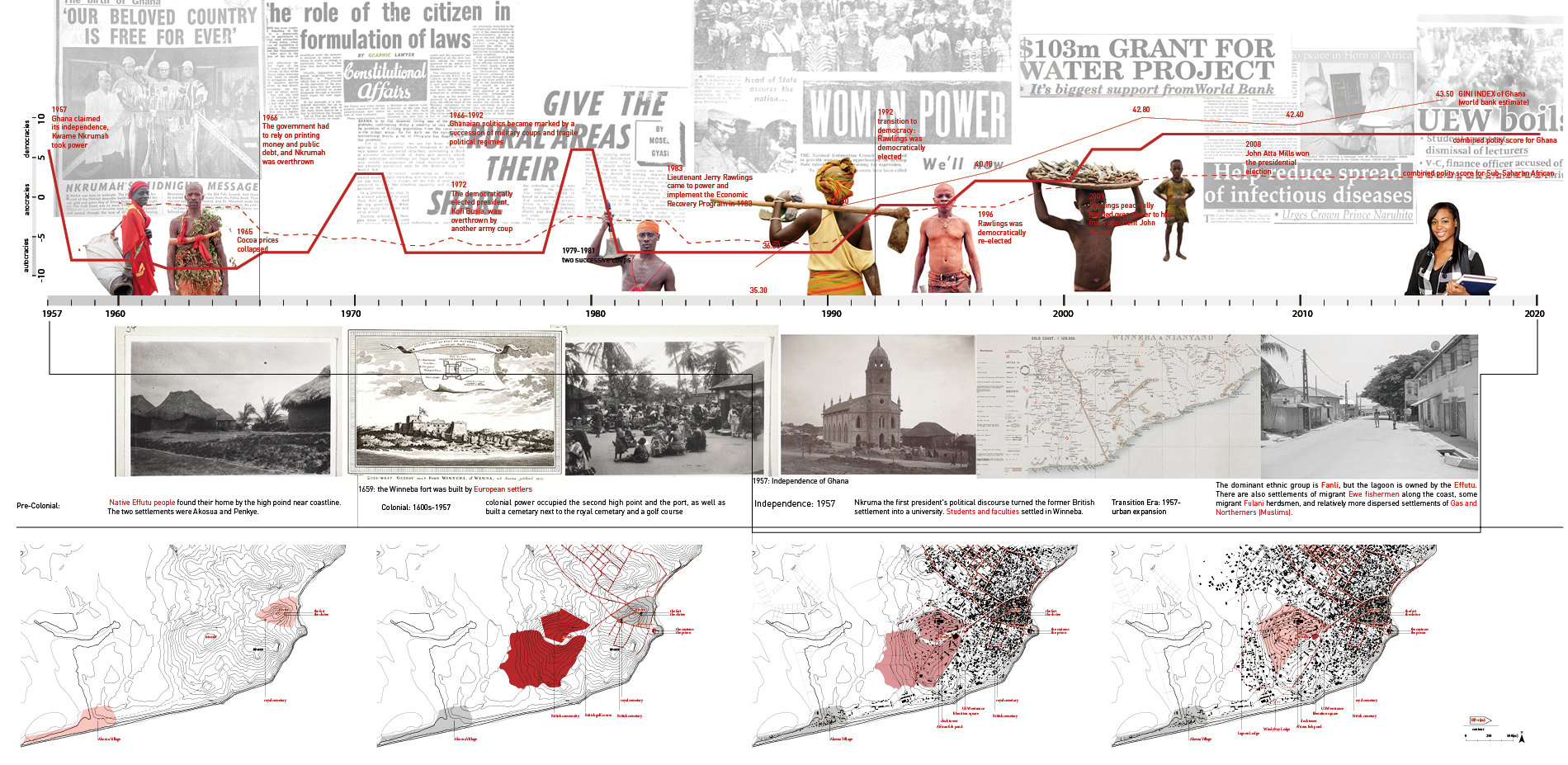

The city of Winneba is located on the Gulf of Guinea in Ghana’s Central Region. Residents have relied on artisan fishing as their main livelihood for hundreds of years. As it expands from a small fishing community to a college town in the 1960s, then to a satellite town of the capital, indigenous Effutu people are joined by migrants from diverse backgrounds. Today, Winneba is a rapidly growing city with a population of 60,000.

However, infrastructure lags far behind the development. People defecate in open areas, domestic wastewater is released untreated into natural water bodies, posing great challenges to environmental and public health. The low level of sanitation delivery, which is partially blamed on inappropriate regulations, is interrelated to social inequity. Tackling social issues is as critical to the long-term management of the water sanitation system as building new infrastructure.

Social conflicts are always impacting this region, such as hostility between native Effutu and other settlers, matrilineal and patrilineal and dual-descent system, succession issues resulted from colonial history. In addition, gender debates are increasingly significant. Females are usually responsible for collecting water and other household chores. In Ghana, 65% of women spend 3-4 hours per day in just collecting water, limiting their education and financial independence.

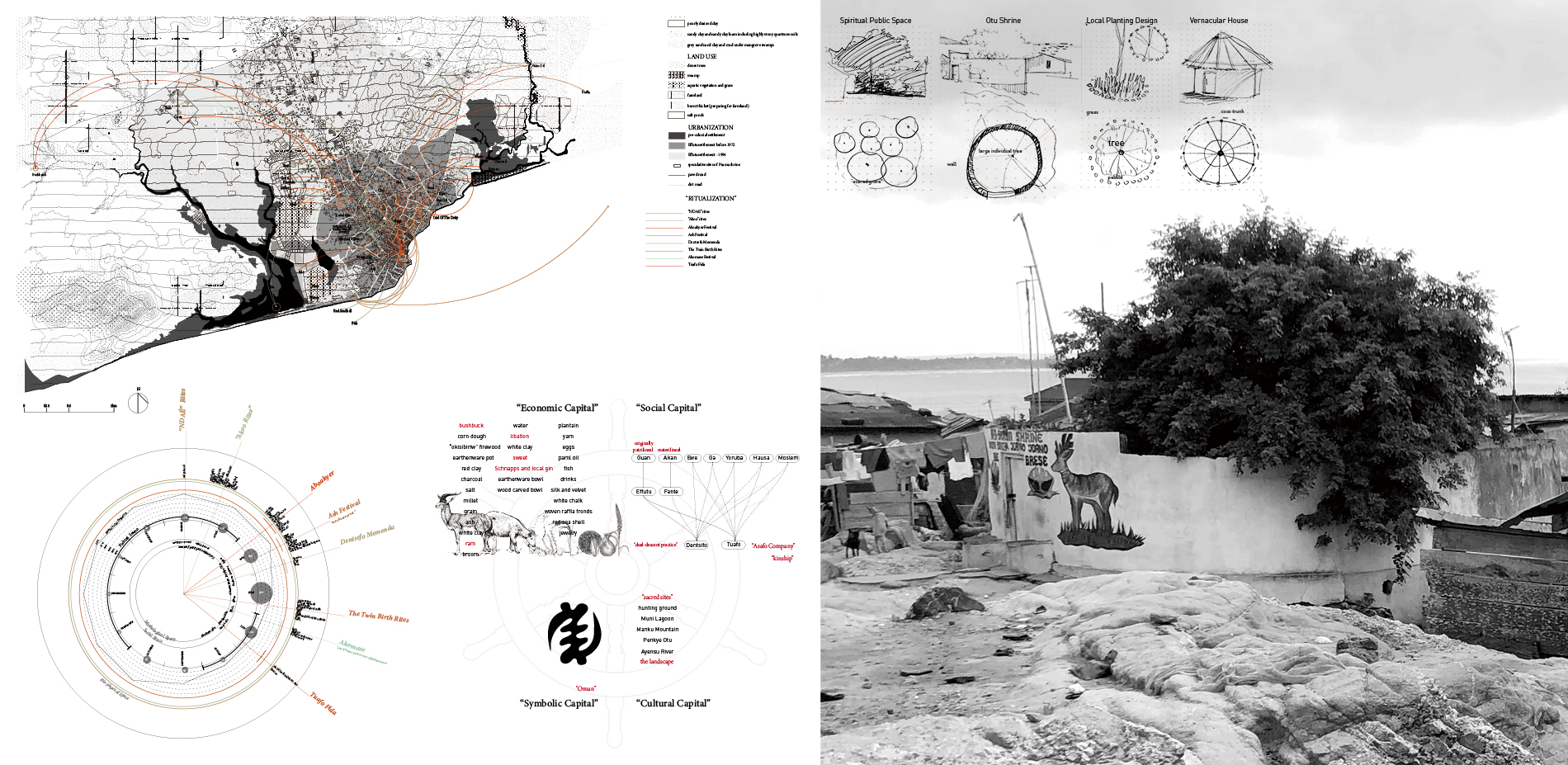

Social power and management policy

Customary practice plays an important role in landscape conservation and social cohesion. Festivals have long been used to celebrate harvest and thank nature’s generosity. Taboos are made by local tribes to protect wetlands and forests. Although in recent years, such cohesion is being shaken by the influx of new arrivals, societal transformation, as well as landscape degradation, the success in maintaining these ecologies through local efforts could still inform better policy-making and management.

One of the most notable cases is the conservation of sacred grove, in which no tree is allowed to be removed as it is believed that the spirit of gods will be disturbed. Sacred groves are dense woods standing out from the field, characterized for their cooling shade, and is used to hold ceremonies or rituals by the public. Each time a clan conducts a sacrifice in sacred groves, its members assert certain principles of social order, such as obedience to elders and chiefs. Caring for the grove is considered part of acknowledging such social principles. In a word, the success in maintaining these landscapes relies on that it responds to current structural power, mediates conflicts between social groups, and shapes consensus among them.

Design program

Drawing inspiration from sacred grove conservation, this project proposed a network of green public spaces, which address social equity and ecological benefits.

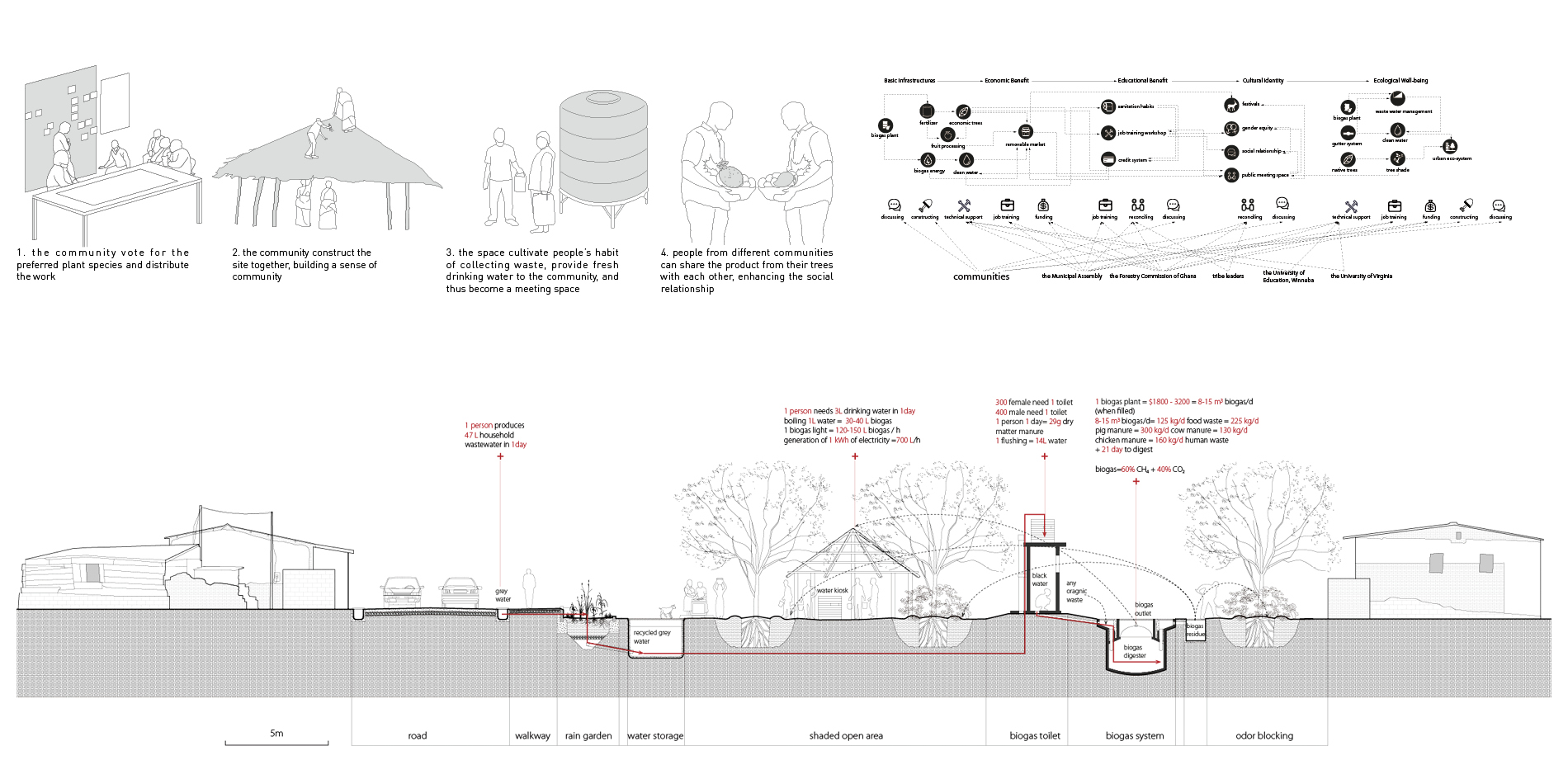

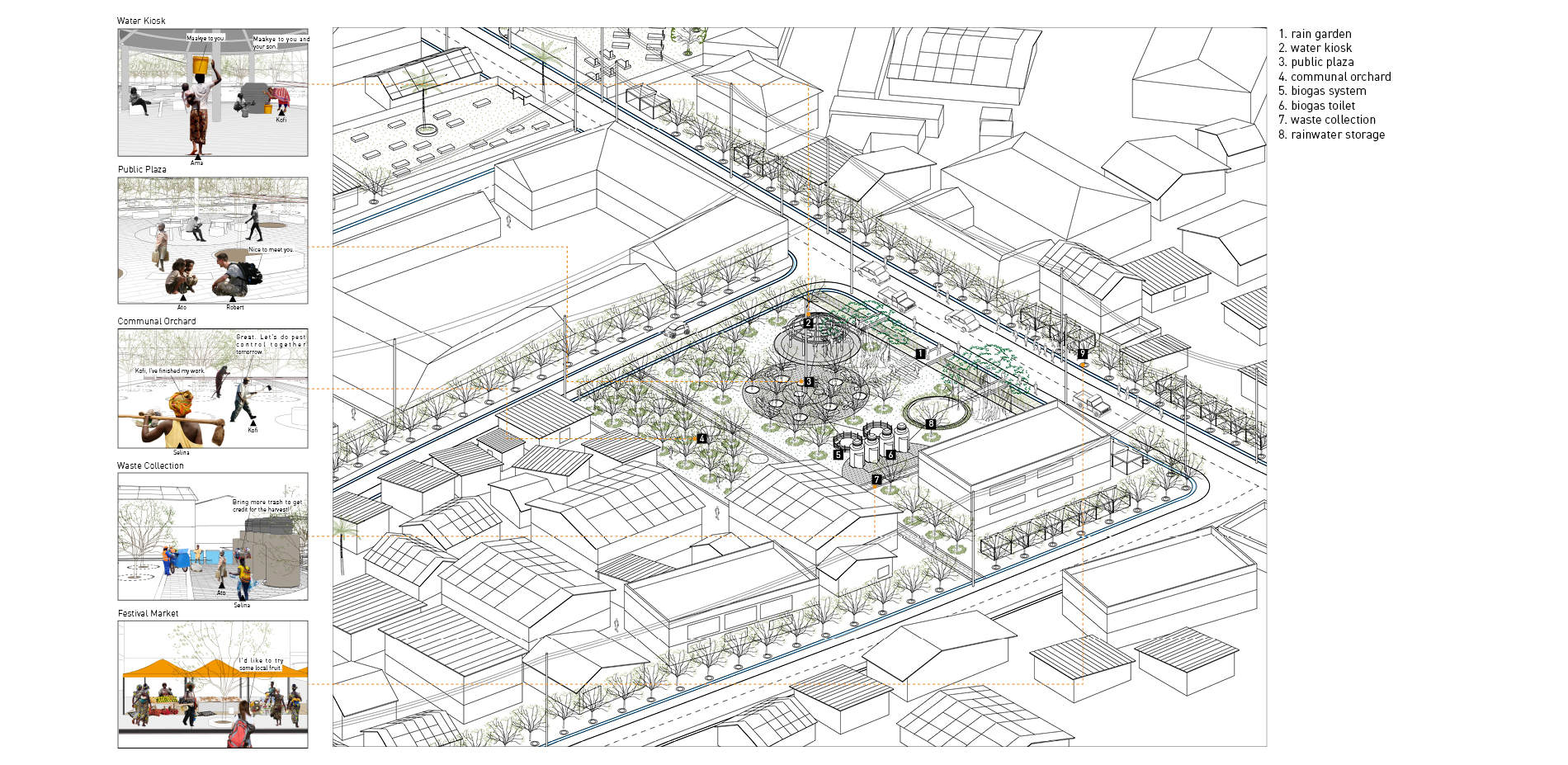

As an alternative to top-down government-led projects, this project calls for residents to build sanitation infrastructures for their own communities. The proposal integrates a gutter system, rain garden, water kiosks, orchard, communal biogas toilets, and waste collection system into its landscape design.

Domestic grey water is filtered and recycled for biogas toilets. Biogas system turns human waste into energy to support water boiling at the water kiosk where people coming to collect clean water can socialize in a traditional way.

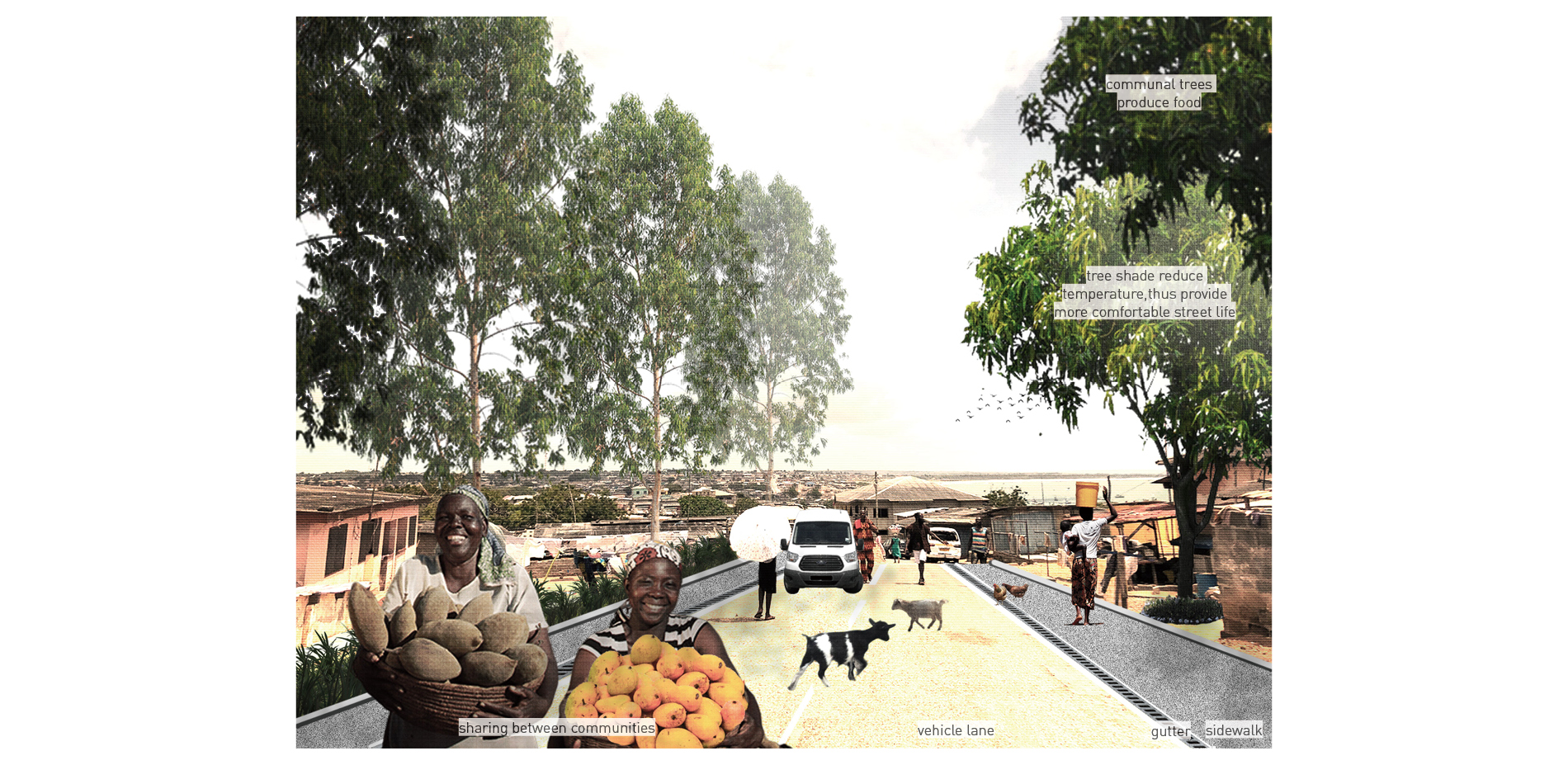

The residue from biogas system fertilizes economic trees that provide well-needed shade and define public space in the densely populated old town. Cultivating, harvesting, processing and selling tree products by locals further boost public activities and street life.

To encourage local participation, a credit system is also included. Residents can gain credit in their account or voucher by using public toilets, bringing organic waste, or taking part in maintenance. Credits and vouchers can be used later to redeem rewards like a liter of clean water, fruits from the communal trees, bus tickets, or school supplies.

Everyone in Winneba is equally welcomed to participate in the project and benefit from it. Shades are introduced to the community. Access to improved water facilities reduces the risks of transmitting disease, releases women from the heavy burden of collecting water. In addition, through collaborative labor, different social groups are brought together to build their community, thus cultivate a cultural identity.

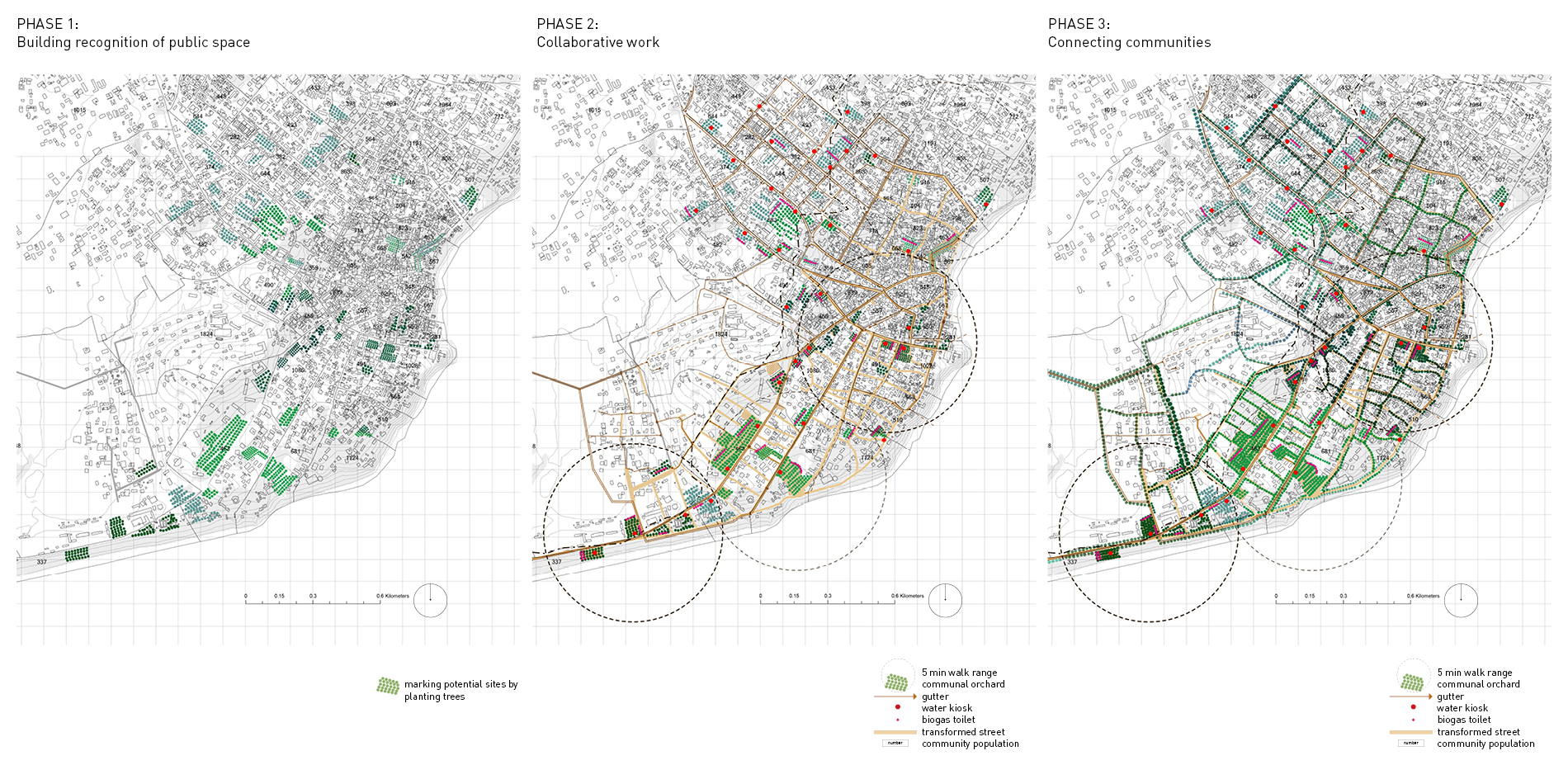

Phasing Strategy

This project is mostly based on bottom-up community participation. A newly established committee made of members from the Municipal Assembly, the University of Education, Winneba, the local tribe leaders, the Forestry Commission of Ghana, and representatives from the University of Virginia will be responsible for funding, advising, training, mediating potential conflicts, and overseeing the whole process.

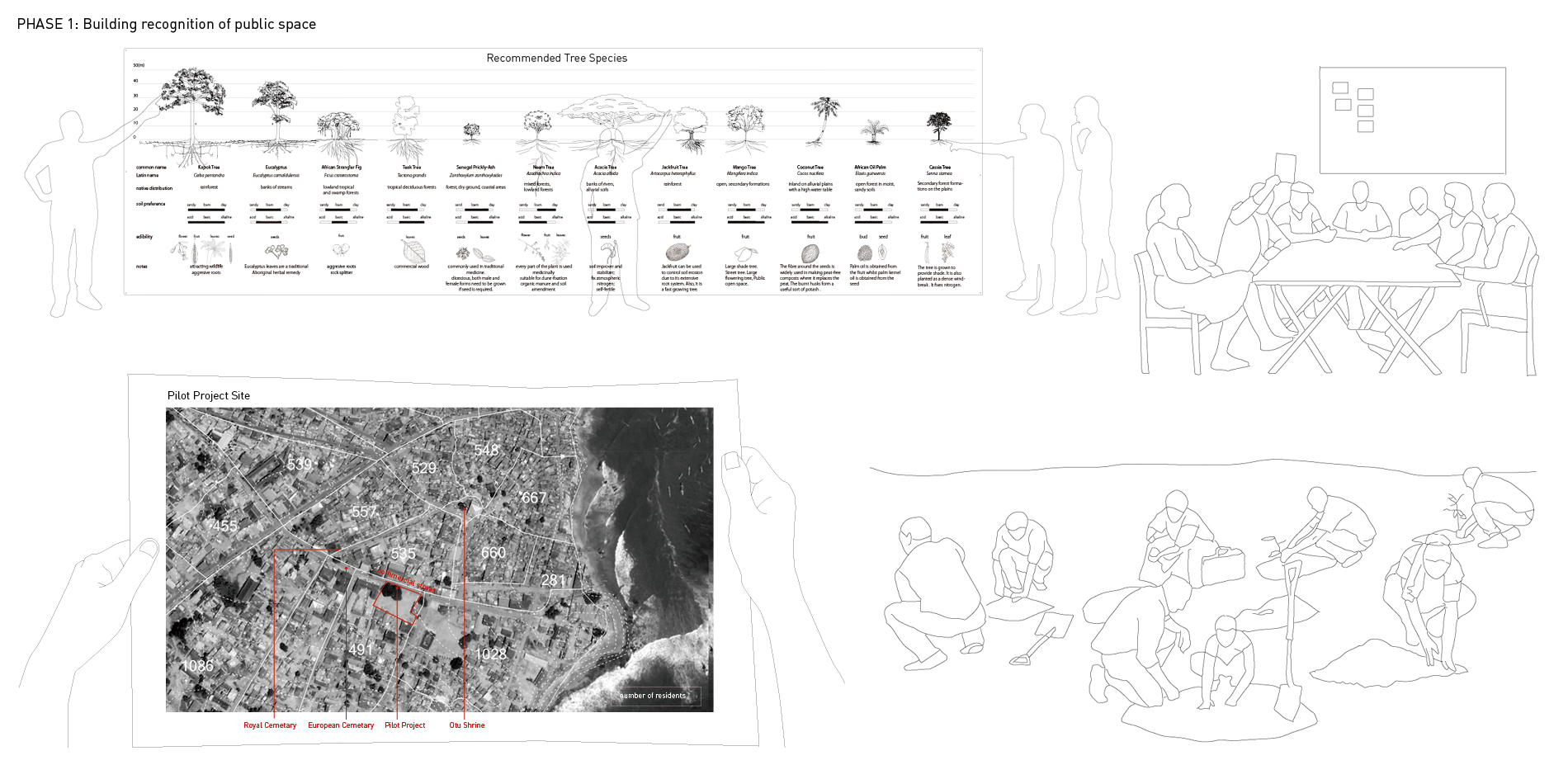

PHASE 1: Building recognition of public space

In Ghana trees indicate the existence of gathering space for many reasons, culturally and sensorially, therefore trees are considered as essential design elements to demarcate the site for public use.

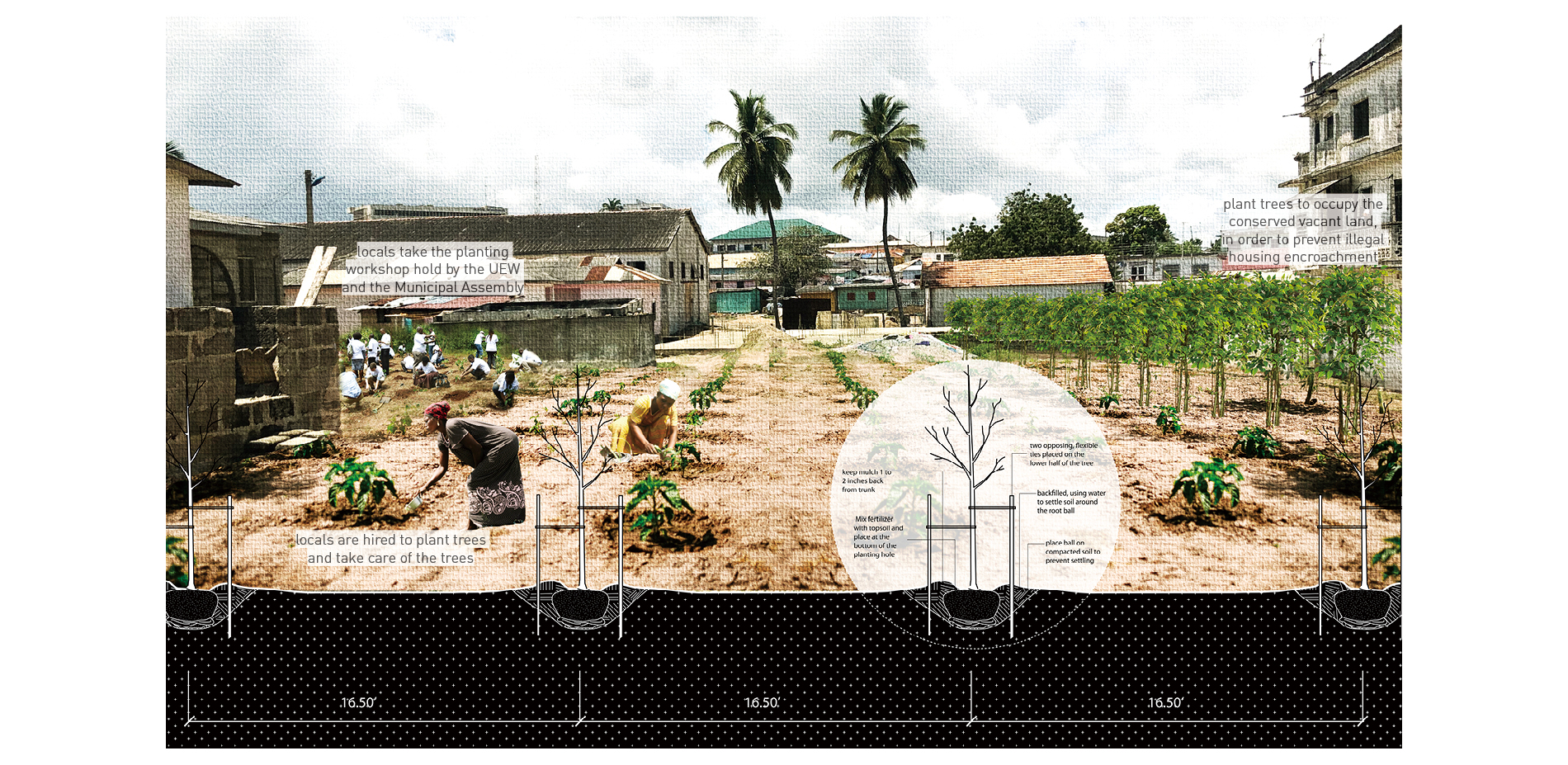

The community will be given a list of recommended tree species. The list includes trees that are tolerant to the local environment and have economic potentials. Residents are asked to vote for their preferred ones and plant trees to occupy the conserved vacant land, in order to prevent illegal housing encroachment. As the trees grow, the groves will become popular meeting space and shelter under tropical sun.

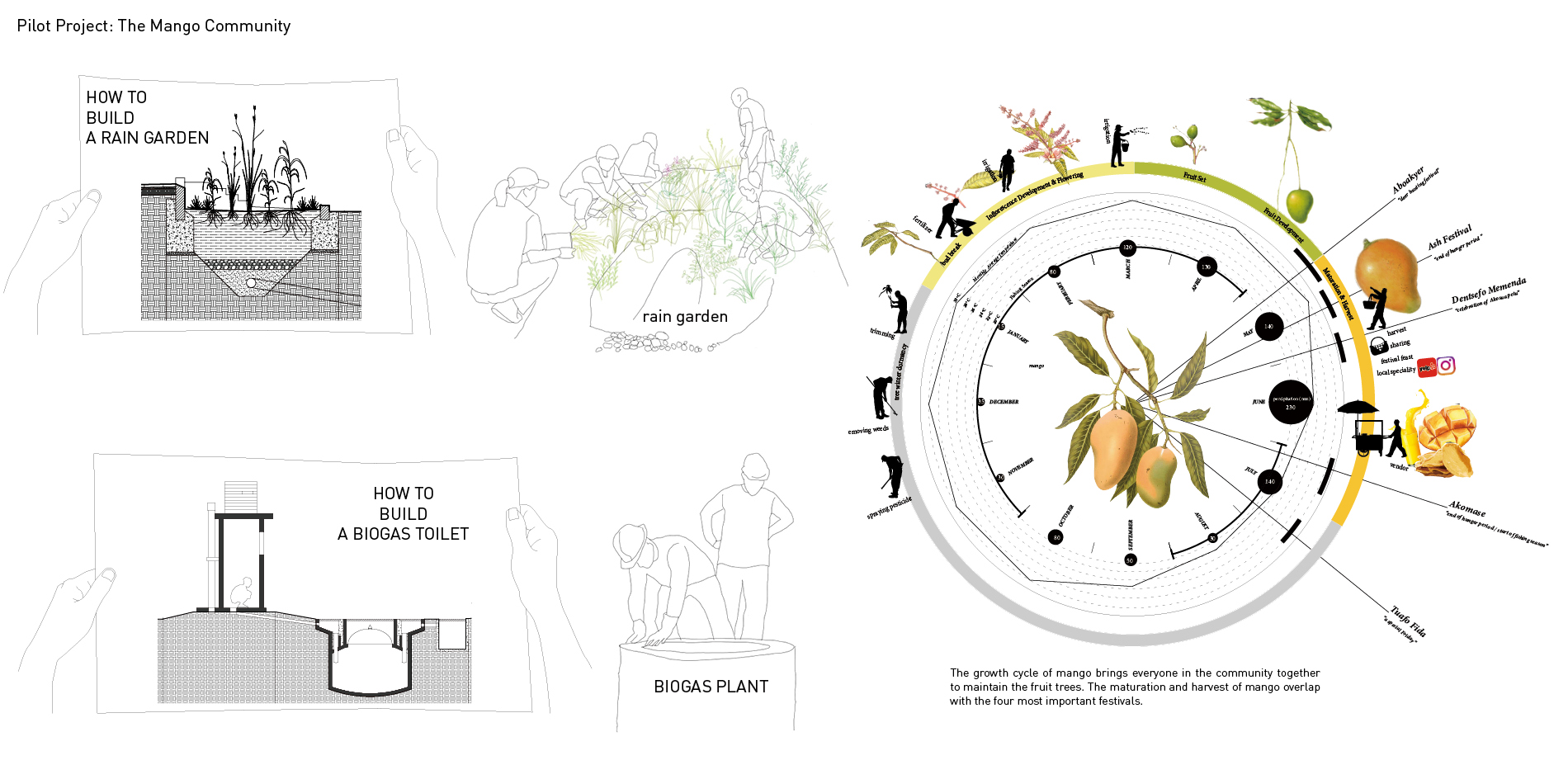

A pilot project will be built in one of the communities near the old town, within five minutes’ walk from the shrine where famous festivals and related animal sacrifices are held. Mango tree has been selected at a local community meeting as the pioneer tree species for the space.

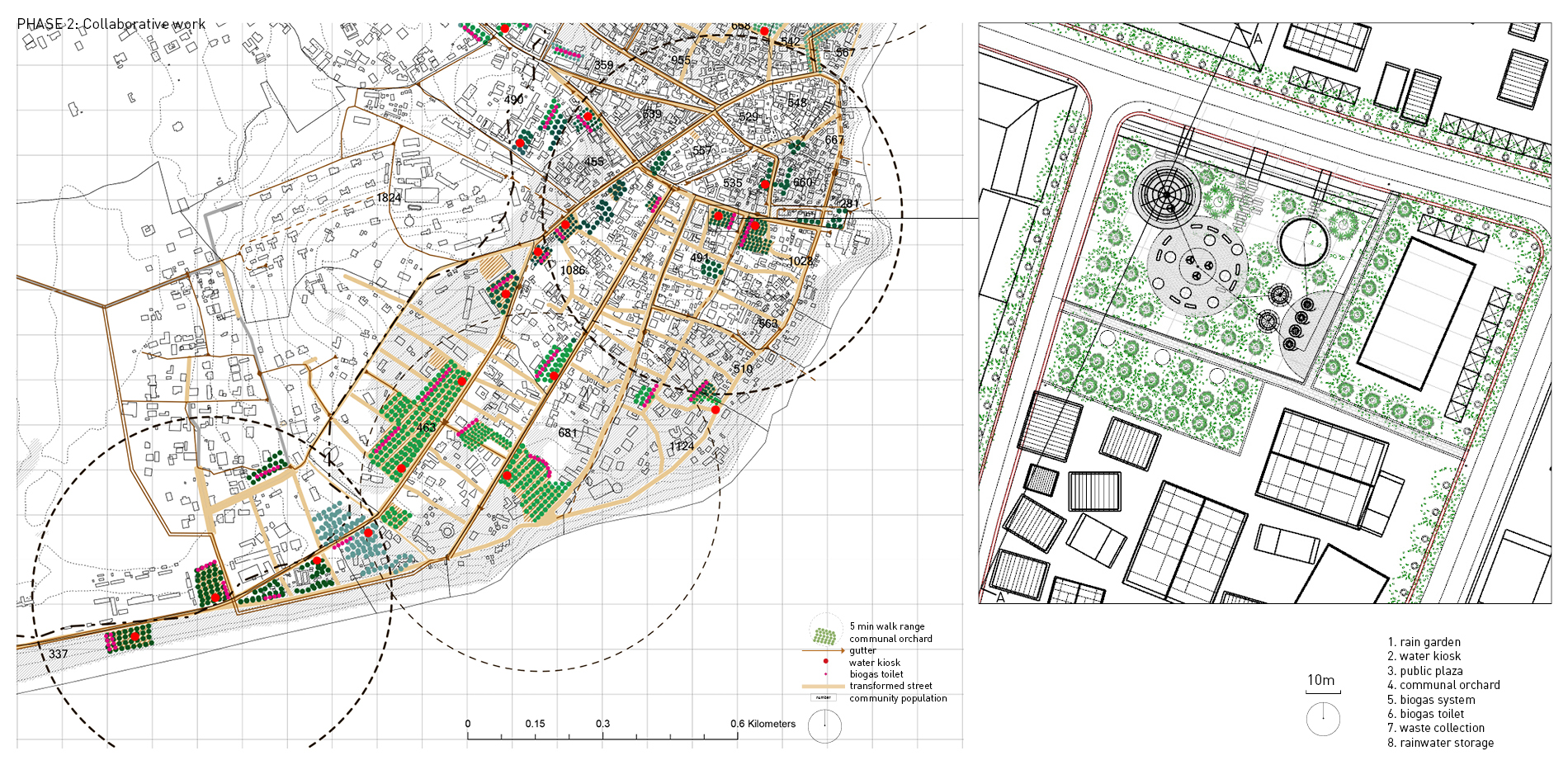

PHASE 2: Collaborative work

In this stage, local meetings are held to discuss on distribution of work. Hiring locals to construct the necessary infrastructures provide them additional job training and most importantly, a chance to cooperate with their neighbors from different background.

In the pilot project, promotion of organic waste collection and biogas toilet systems cultivates people’s sanitation habits. The water kiosk with biogas light will be the first lighted public space at night around the neighborhoods. Mango trees are fully grown in 3-6 years. Maturation and harvest of mango overlap with the four most important festivals in Winneba. People may collectively harvest the mango fruit, enjoy the fruit and sell them along the street.

Work related to gardening or food processing is usually considered to be women’s job in Winneba. In this process, women, who are usually expelled from the dominant fishing industry and lack financial independence, will be provided an alternative livelihood.

PHASE 3: Connecting communities

The third stage will happen when other communities take part in the project. Two adjacent communities need to discuss how to connect their projects, such as the gutter system and street trees.

If this project covers more and more communities in Winneba, the planted streets will be connected as a green corridor with diverse tree species. There will emerge a connected gutter system, with rain gardens to filter waste water. Every small grove in the city indicates the existence of public space with water sanitation facilities, waste collection and economic tree planting.

Development and Impacts

The town planner in Winneba, Isaac Adoah, has already expressed interest in such small scale, affordable urban projects, and will mark available land parcels and identify pilot communities.

Drawing inspiration from customary practice, this innovative public space system catalyzes accumulating social capitals and mediating powers, in a way similar to the traditional sacred sites did. Under a shifting historical context, this project takes new social dynamics into consideration, promoting a more inclusive way of living together. It tries to legitimize minorities’ access to resources by joining their efforts in all three phases. On the other hand, by leveraging collective labor to construct and maintain the functional public space and water sanitation infrastructures, it offers an integrated management strategy tackling the crucial part of long-term feasibility.