News

Interview with Steven Nygren, Founder of Serenbe

Steven Nygren / Serenbe

Steven Nygren / Serenbe

You founded Serenbe, a 1,000-acre community in the city of Chattahoochee Hills, which is 30 miles southwest of Atlanta, Georgia. In Serenbe, there are dense, walkable clusters of homes, shops, and businesses, even artists’ studios, modeled like English villages set within 40,000 acres of forest you helped protect. Can you briefly tell me the story of this community? What motivated you to create it?

It was a reaction. We purchased 60 acres in a historic farm in 1991 just on a weekend whim while on a drive to show our children farm animals. It seemed like a good investment. I wasn't sure why we were doing it other than my wife and three daughters thought it was a great idea. To my amazement, every Friday when I got home, everyone was anxious to leave our big house with the pool, the media room, and all of the trappings, to go out to the country. Watching the difference in the children and our own family on those weekend times, I decided after three years to sell the company, sell the big house, and retreat to this rural area, right on the edge of Atlanta.

Seven years later, on a jog, a bulldozer was bulldozing the forest next to us. At that point, we owned 300 acres. We were fearful that the threat of development was coming. It turns out they were clearing it for a small runway for one of the neighbors. But that set me on the path of thinking what could happen.

At dinner one night when I shared my concerns with Ray Anderson, the founder of Interface Inc, who had been a good friend, he said, "Let's bring the thought leaders in to talk about this." So in September 2000, 24 people invited actually showed up -- because of who Ray was -- for a two-day conversation facilitated by the Rocky Mountain Institute, documented by Georgia Tech. At that point, I went into the session interested in how we could protect our own backyard, but I came out with an understanding of how serious the issues are. And you realize in September 2000, the first LEED building hadn't been certified.

A lot of the things we take for granted today were way over the edge thinking just a decade and-a-half ago. We began looking at what could be done. We decided that most models ended up being magnets for what they were trying to change. We set about to bring land owners together in a 40,000 acre area.

How did you and the other members of the Chattahoochee Hill Country Alliance achieve buy-in from local planners and policymakers to create Serenbe and the broader Chattahoochee Hill Country Community Plan, which protect 40,000 acres of nature from Atlanta’s ever-engulfing sprawl?

We realized we needed to create a larger vision than just buying land and trying to create a model. We brought everyone together over food. We invited the largest land owners to dinner, and after several cases of wine and several good dinners in our home, we thought we had buy-in. Next, we expanded the ring to get buy-in from owners representing 51 percent of the land.

That meeting would have reminded you of the worst zoning meeting you've ever sat through. Within an hour and-a-half, we had people calling each other names, even neighbors who had known each other through generations. So I realized that it was a much bigger issue. Half of the people who inherited land wanted the bulldozers to come because this meant payday, and the other half didn't want the land touched. It was between the land speculators and us, who had found this paradise.

We put together some more research. I first reached out to a community leader who was also a property rights advocate to get agreement to come to another meeting. About ten minutes into the call, he said, "are we going to have that peach cobbler?" And so my wife kept baking and cooking and we kept calling meetings. Then that proceeded into a public process with all the landowners, over 500. It was a two-year process. By late 2002, we passed the largest land use plan in recent history in metropolitan Atlanta, with 80 percent of the landowners paying dues into the organization we formed, with not one word of opposition. It was quite remarkable.

There has been a long history of utopian agricultural communities. Early communities in the U.S. and Europe came together for ideological reasons. They were anarchists seeking self-sufficiency, proto-communists or socialists seeking to bring social reform to serfs, and others farming to just improve human health and well-being. Some of the early communities in turn influenced Ebenezer Howard, who created his Garden City movement right before the turn of the 20th century. Where do you and Serenbe fit into this rich history?

When you look over time, you'll see there has been a constant tension between rural and urban. But also each of these movements have responded to the issues of their time.

Serenbe certainly represents a turning point to counter Atlanta's sprawl, which is terrible. Marie and I were urban people who believed we should develop where infrastructure exists. But at the point we got involved a decade and-a-half ago, over 70 percent of the development continued to be in greenfields. There were no good models.

Serenbe deals with the issues of our time: how do we create communities that connect urban and rural, the city and agriculture? I would like to think that history will look at Serenbe as part of a movement that returns development to responsible uses of resources in a balanced way.

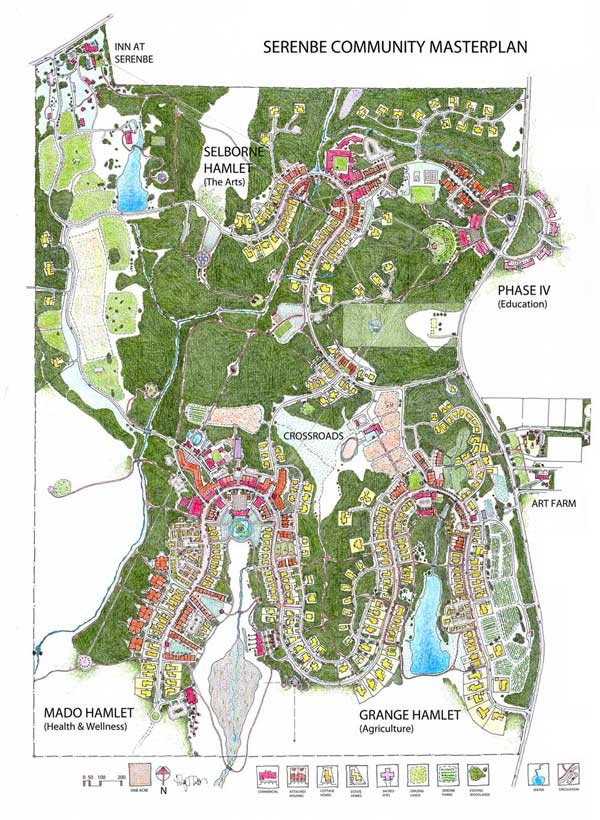

The Serenbe community has a unique layout, with “serpentine omega forms.” What ideas guided the plan?

Phil Tabb worked with us as a consultant. He did his doctorate on the English village system and was also trained as a sacred geometrist through Keith Critchlow. We wanted to achieve a complete balance, very much what biomimicry pioneer Janine Benyus talks about. In nature, everything is balanced. But as developers, we don't always respond to nature in a real way.

When Phil and I first started walking the land to understand the assets and restraints, we talked about the ridges for house clusters. We were thinking about the hill towns of Italy, where we both visited. Then when we came together for our first two-day design charrette. It became obvious that we wanted to save those ridges for public natural access. We could locate the density and the housing in the valleys, which brings you down. If you come into the valleys, you come by the streams. To really work with the streams, it became an omega -- you had one crossing, with the housing on each side of the stream. The omegas really emerged through our understanding of the land. The land spoke to us and and we saw where we could locate buildings with the least disturbance, and yet, really bring the land to life. At Serenbe, houses are nestled around the water, with this wonderful little stream down through the center. All the ridges have community paths.

Serenbe masterplan / Serenbe

Serenbe masterplan / Serenbe

Various movements claim Serenbe. We relate to each of these movements, such as the New Urbanists, the farm-to-table movement, the environmental movement. We are all of these things but we're much more than any one of them. One of the areas where we differ with the New Urbanists is the grid. Our grid is pedestrian, not vehicular. There is a complete grid for pedestrians going across the streams and omegas, but our streets wander. We were really in the forefront of the movement to get people out walking, because at Serenbe you can usually walk to places in half the time that the road will take you around here.

In an interview with the journal Terrain, Ed McMahon, a senior fellow at the Urban Land Institute, said “agriculture is the new golf.” The new desirable amenity is a well-maintained farm. The benefits of a community farm are food production, new revenue, and even tax breaks for preserving farmland. How do the residents of Serenbe pay for its 25-acre farm? How is the farm maintained?

When we started Serenbe, you really didn't see farms integrated into a community. And you know, Ed was one of the early people that I turned to. The Urban Land Institute (ULI) had just released a study that said 92 percent of the people who bought golf course lots -- at that premium bankers adore -- played golf less than twice a year. They were buying the green space, the open space.

When I was trying to fund Serenbe, I would talk to the bankers, and say, "OK, if that's true, wouldn't people pay the same premium if not more to back up to a farm or a pasture?" There were no statistics to show that, so the financial community wouldn't fund the development. The real estate community was dubious. So was Andres Duany, who didn't think people would live that close to smelly farms. We are delighted that he is now a big supporter of this movement.

We were really pushing this idea of agricultural integration. We realized a lot of the negatives that "big ag" farms have. But a small organic farm is charming. We really pushed forward with these ideas, even though our land had been stripped of nutrients through the cotton monoculture, so it didn't look like it could produce. Everyone said, "You're nuts. You're crazy." But it seemed like such a core thing: if we were going to create a balanced, sustainable community, food was one of the critical things, along with energy and water.

Serenbe aerial view / Serenbe

Serenbe aerial view / Serenbe

Now, we operate Serenbe Farms as a teaching farm. I had initially decided we would be self-sustainable in five years. It was self-sustainable in three years. We 25 acres set aside and about half of that is under active

cultivation, with cover crops on the other half. The farm supplies our

three restaurants. We have a great CSA program for people outside

Serenbe. There's a farmer's market on Saturdays.

We have a farmer hired on a base salary, and then they get a profit based on what they make. We have an intern house with four interns. The farmer makes a very nice salary and it's profitable, and educational. So we're growing farmers as well as crops.

Serenbe organic farm / Serenbe

Serenbe organic farm / Serenbe

Is a model like Serenbe only for the relatively well-off? Can you conceive of this model working for middle or working class communities? Our model is essential for lower income groups. One of the critical problems in our educational system is that we're not teaching people how to grow and prepare their own foods. It should be one of the basics of the education system and it's just not. It takes very little land to grow all the foods you need for a family.

We've been able to demonstrate at Serenbe that with five acres, one member of a couple both working and paying for daycare can leave the workforce as we know it and actually tend the farm. That couple can have a higher quality of life. It's essential thing that we have farmers in smaller lots growing local food.

Now, let's talk about the labels organic and local. We've had to label these things because we've gotten so far away from the basics of 50 to 60 years ago. Then, we didn't have organics, we had good nutrients. That's what we have to get back to.

With our CSA program, a family of four can have all the vegetables they need for a week in the key growing seasons. How much does that cost a day? $4.80. That's affordable. So this idea that fresh fruits and vegetables are not affordable is crazy.

Wholesome Wave is a fabulous program. Michel Nischan started five or six years ago. It's one of the few programs that received increased funding in the recent Farm Bill by both Republicans and Democrats. For every dollar raised, the Farm Bill matches it by a dollar fifty. It's for anyone on SNAP programs. If lower income folks are getting food assistance, they can turn $20 of credit into $50 dollars of fresh fruits and vegetables from a local farmer. This is stimulating the local agrarian economy, and getting fresh food into homes.

In Serenbe, sustainable homes are set close together in New Urbanist arrangements. The organic farm stores carbon. Water conservation is enabled through water-efficient appliances and green infrastructure. Waste water is treated through a natural system designed by landscape architects with Reed Hilderbrand. Yet, most of the 400 residents of your community drive to work in Atlanta, and the thousands of visitors you get each year also drive there. How does this balance out in terms of overall sustainability?

Serenbe development street / Serenbe

Serenbe development street / Serenbe

Serenbe's natural wastewater treatment system by Reed Hilderbrand / Serenbe

Serenbe's natural wastewater treatment system by Reed Hilderbrand / Serenbe

The perceptions that everyone is driving out to work is mistaken. A

recent survey we did showed that 70 percent of the people living at

Serenbe worked all or part-time at home. We have moved away from the

time when everyone arrives at a desk at 9 and leaves at 5. For

some of our residents, the airport is their key means of transportation;

they're consultants or what have you.

We did also a survey asking if people drove more or less since moving to Serenbe. We found we're just right on the edge of the same trends. When they lived in the city, everything seemed convenient, and so they were constantly going out for trips. In Serenbe, they're more organized and they really don't leave as much. With Amazon and so much e-commerce, we can live in a different way.

We are also creating jobs in our shops, restaurants, and other service sectors. People who already lived in the area around Serenbe were traveling great distances for jobs. We have created this entire local job force for people who are already living nearby. If you look at the net, we're probably cutting down on trips.

The New York Times recently wrote about the country-wide growth of communities like Serenbe, which they call “agrihoods.” How can you explain their growth? But, also, given these communities are still far from mainstream, how do you explain their still limited appeal?

I believe that all trends begin and then grow. There is no way to walk through a threshold from no appeal to total appeal. When we put our first development in just 11 years ago, the idea of farming in a new community just didn't exist. The fact that it's even in the conversation a decade later means there's a lot happening. But this is not a model in which the majority of Americans can live. That just isn't feasible.

The broader movement that needs to happen is finding an authentic way to bring more food sources into our mainstream developments. At Serenbe, the crosswalks all have blueberry bushes.

Serenbe edible landscape / Serenbe

Serenbe edible landscape / Serenbe

Why shouldn't that be happening in any urban area? Where we're sitting here in Austin, why are these pots filled with ornamental plants that have no meaning? Why aren't they full of herbs or something the kitchen can use? Our movement can help edibles integrate into our typical landscapes.

Finally, there's an understanding that we need to daylight more of our stormwater. Wouldn't it be incredible if all of our urban areas had these veins of bio-retention to capture our stormwater and beside those systems were edible landscapes? This is where I want to see us moving to.

The agrihood idea is waking people up to the benefits of having food near where you live, but let's integrate those ideas into mainstream communities.

Steven Nygren is the founder of Serenbe, which has won numerous awards, including the Urban Land Institute Inaugural Sustainability Award, the Atlanta Regional Commission Development of Excellence, and EarthCraft's Development of the Year.

Interview conducted by Jared Green at SXSW Eco in Austin, Texas.