Rethinking a Fundamental Human Act: Landscape as a Solution for Open Defecation

Award of Excellence

Urban Design

Kate Noel, Student ASLA; Xiaoyu Zheng, Student ASLA

Faculty Advisors: Alpa Nawre, ASLA

University of Florida

One of the most basic human needs is sanitation, and solving this issue goes a long way toward addressing health, dignity, inequality, and poverty. This proposal for Raipur, India, provides sanitation facilities and serves as a case study for other vulnerable populations worldwide. A phased approach begins with defecation management during the establishment of public toilets and culminates in the installation of household facilities that connect to previous phases’ infrastructure. Proposed interventions account for current defecation habits, attempting to weave those habits into a design for a shared structure that captures rainwater for cleansing and waste treatment—all while instilling health benefits of hygiene for individuals and their collective landscape.

- 2020 Awards Jury

Project Credits

Photographer

Cody Artzner

Project Statement

524 million people practice open defecation in India. Open defecation perpetuates the vicious cycle of disease and poverty leading to child mortality, malnutrition, social inequity, and violence against women and girls. In this context, there are few spaces of conscious design intervention that provide both practical and aesthetic value. We explore how landscape architects can improve the lives of people that lack basic facilities through our design of the built environment. Our goal is everyone will have access to personal toilets in each household and public toilets in community spaces.

This project introduces sanitation facility designs and phasing in Raipur, India. We propose design solutions based on a theoretical framework highlighting causes, conditions, and effects of open defecation. Our designs can be replicated in other vulnerable communities outside of India that also suffer from poor or absent sanitation infrastructure. By working for communities that lack even basic necessities in a landscape with little consideration for the built environment, this proposal challenges our own notions of what design can do for human beings.

Project Narrative

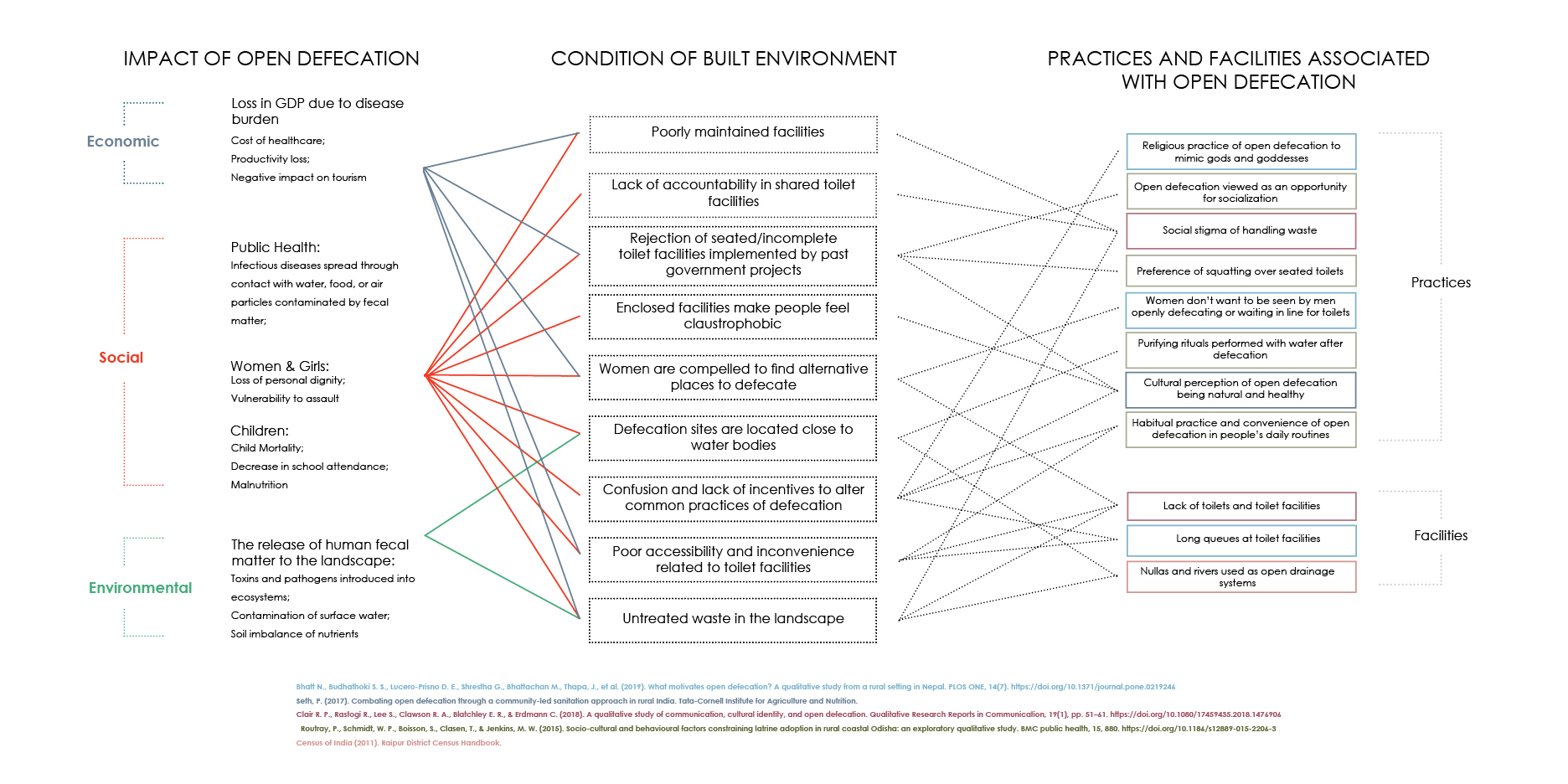

UNDERSTANDING OPEN DEFECATION WITHIN THE REALM OF SOCIETY, ECONOMY, AND ENVIRONMENT

About 1.1 billion people practice open defecation in the world, most often in areas lacking sanitation infrastructure and services. Open defecation has lasting impacts on the social, economic, and environmental integrity of a community. It threatens personal dignity, public health, financial resources, and the landscape itself.

By examining current literature regarding sanitation in India, we discovered relevant practices and facilities issues associated with open defecation, which included cultural preferences, habitual acts, and overall lack of resources. To bridge the causes and impacts of open defecation, we connect these concepts to the current conditions of the built environment. As of right now, the state of the built environment does not meet the needs of the people it is intended to serve. Our proposed design solutions correlate to the poor conditions we identified.

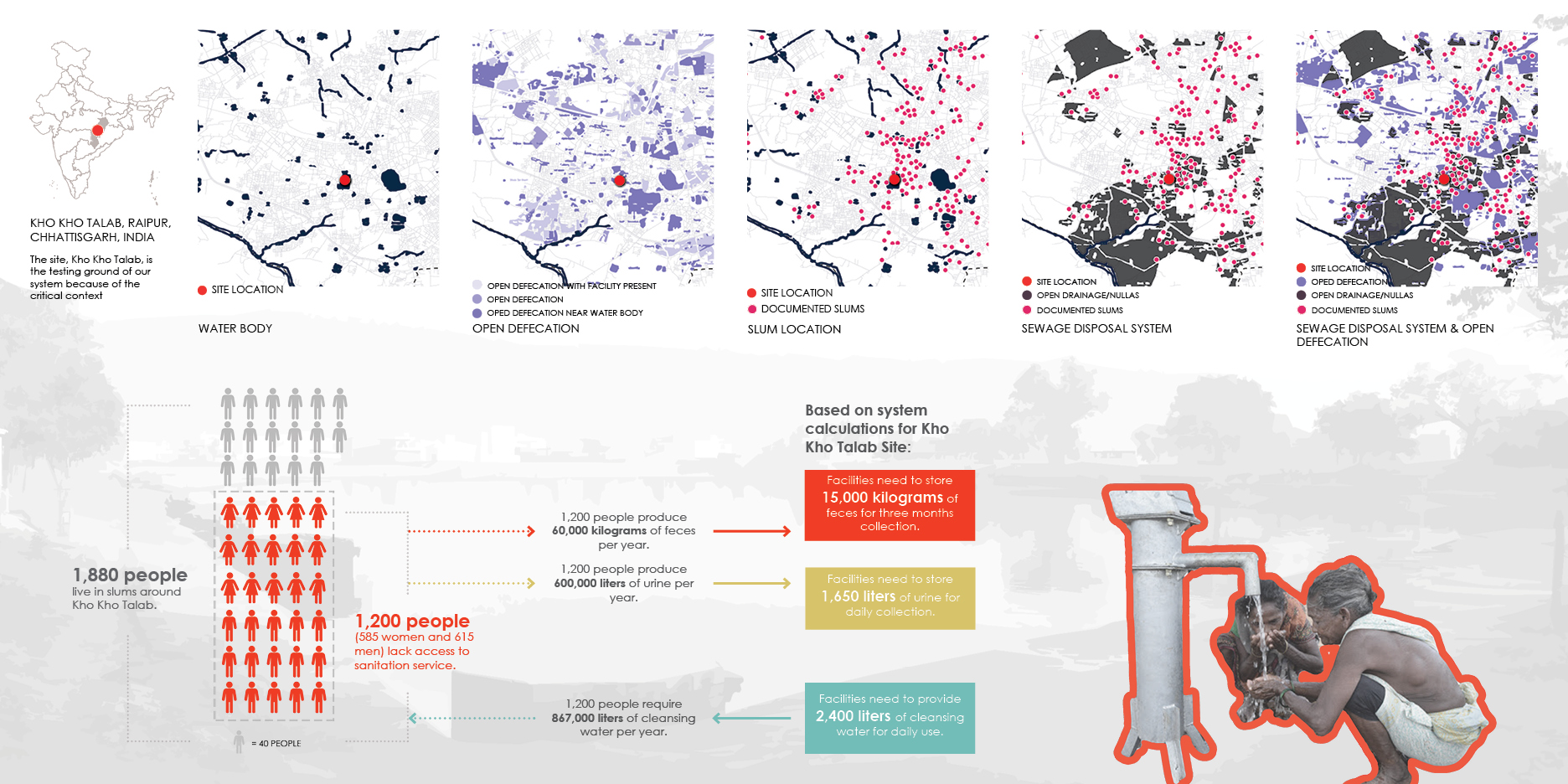

THE CONTEXT OF RAIPUR, INDIA AND THE NEEDS OF THE PEOPLE

Our project site, Kho Kho Talab, meets at the convergence of several key issues discovered through data acquired though the Raipur Municipal Corporation. Contextual maps show the intersection of water bodies, sanitation access, slums and informal settlements, and open drainage (nulla) systems. All of these factors lead to increased open defecation rates. During a student site visit to Kho Kho Talab, people openly defecating in the water were observed.

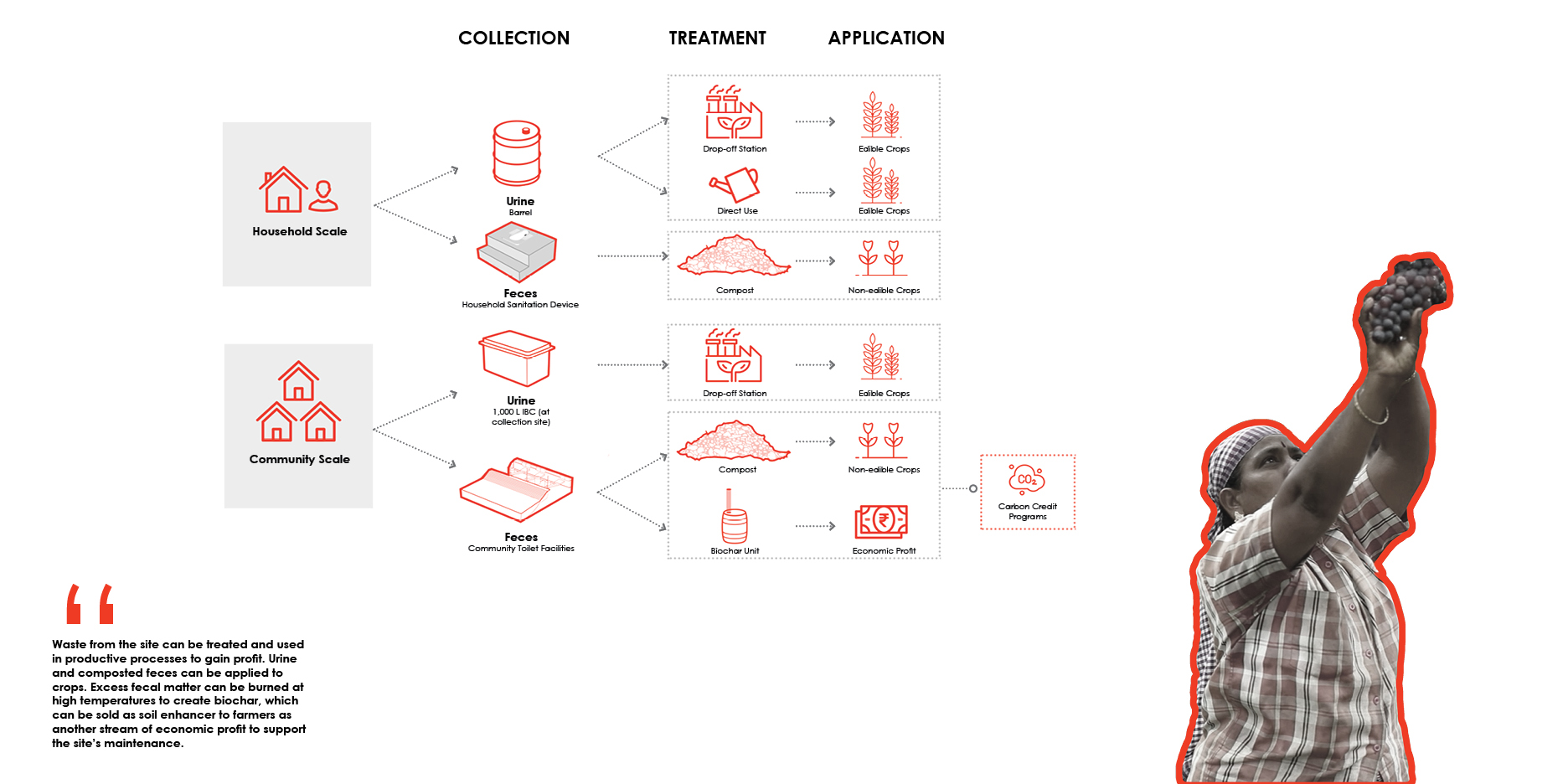

According to the Chattisgrath Census of 2011, about 1,800 people live in the slums around Kho Kho Talab in Raipur, India. Of that population, about 1,200 people lack access to sanitation services. This critical number of 1,200 people informs the size and scope of our design interventions. We calculated the average production of cleansing water, urine, and feces based on 1,200 people per year. Based on collection and storage methods, we concentrated the flow of waste on a daily basis as applied to cleansing water and urine and on a three-month basis for fecal matter.

TRANSITIONAL PHASING TO ELIMINATE OPEN DEFECATION

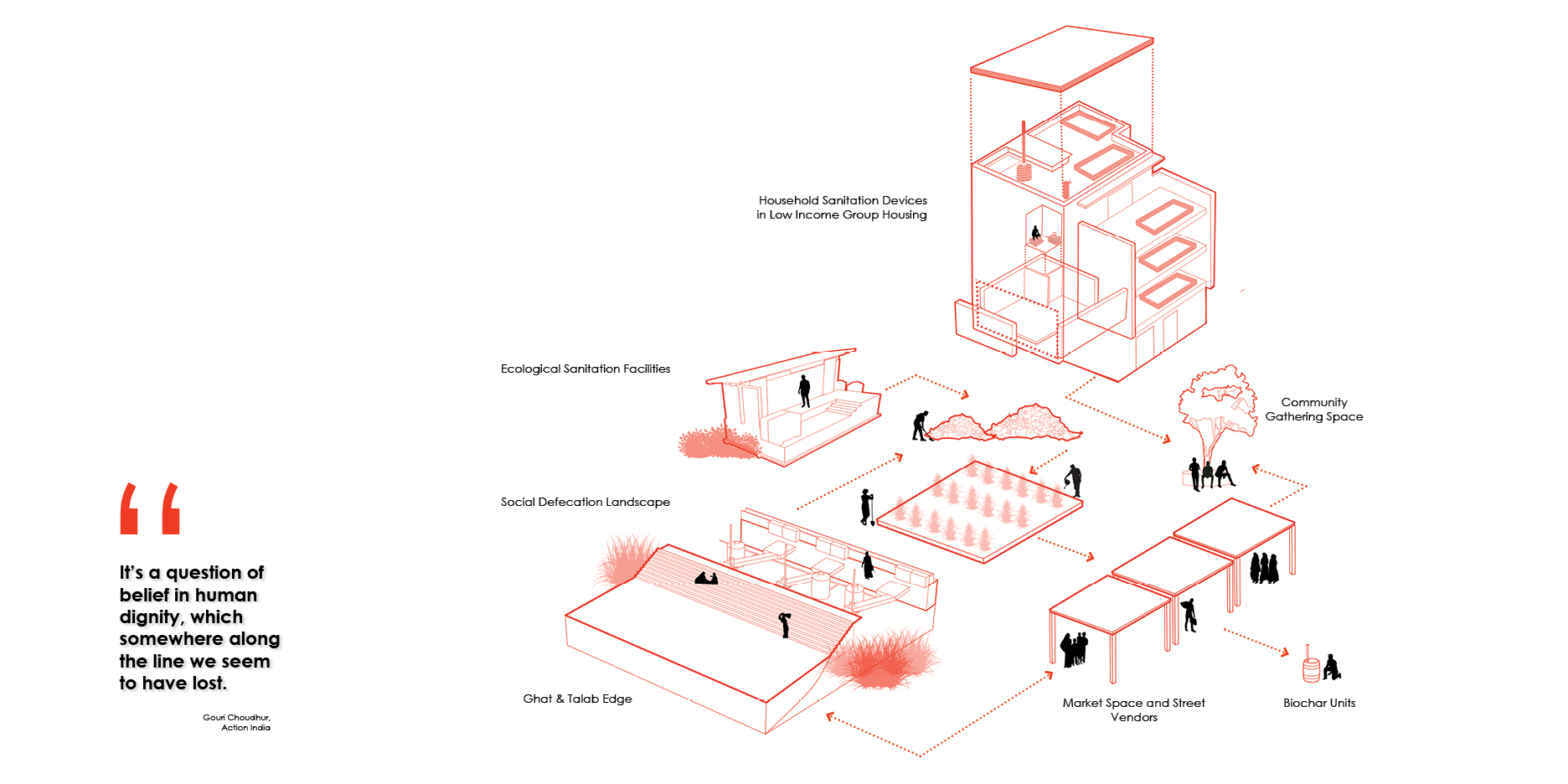

To meet our final vision of everyone having access to personal toilets in each household and public toilets in community spaces, we have designed three separate sanitation facility components to transition to managed defecation. Each component is present in the three phases outlined to meet our goal by the end of the century. Phase I focuses on community facilities that weave defecation management into the existing landscape. Phase II is the intermediary phase that addresses the need for permanent public toilets. Phase III culminates with the establishment of private household sanitation integrated with public toilets, all operating within the framework of a community-scale network of waste management.

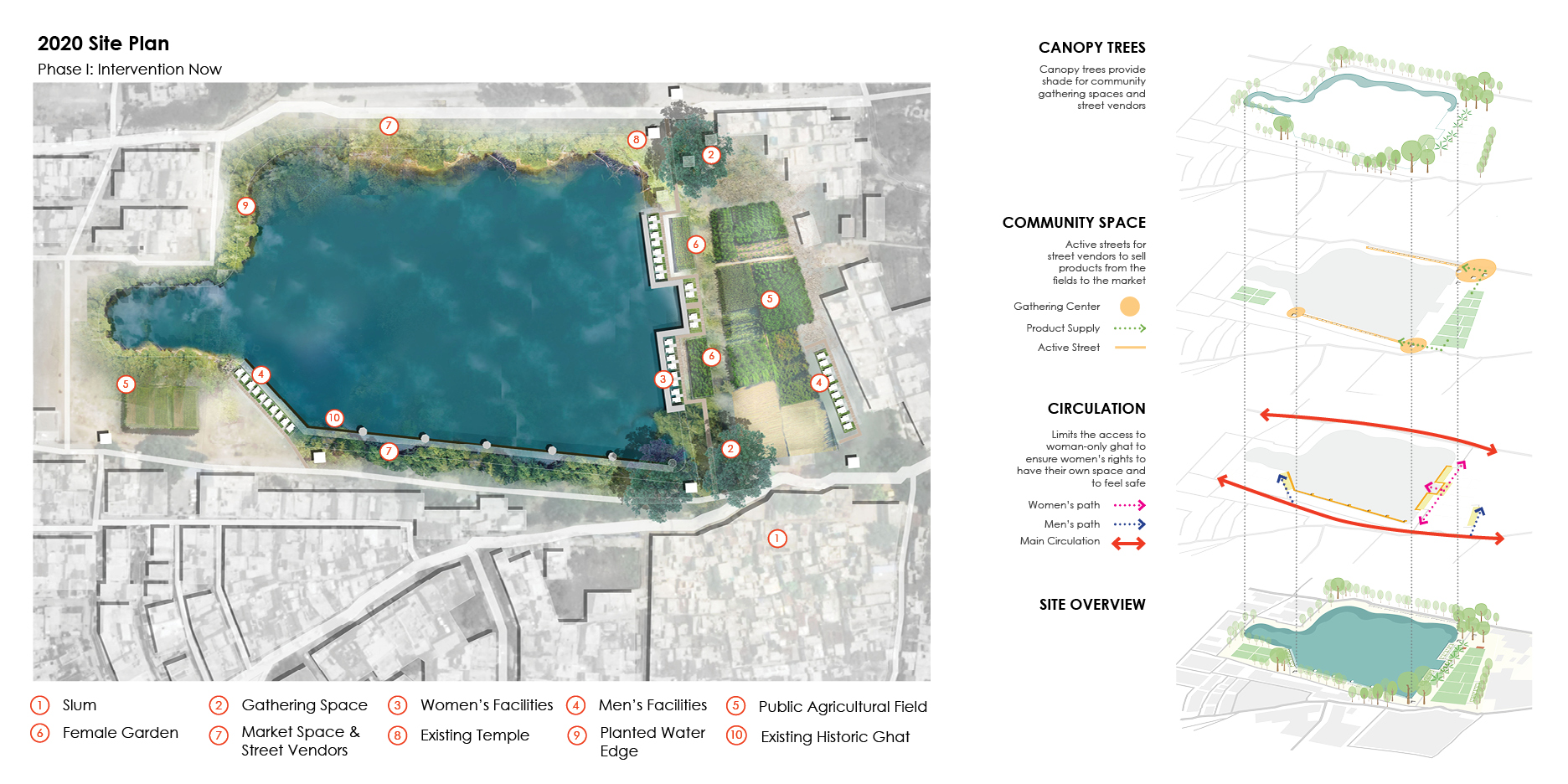

SITE PLAN OF KHO KHO TALAB

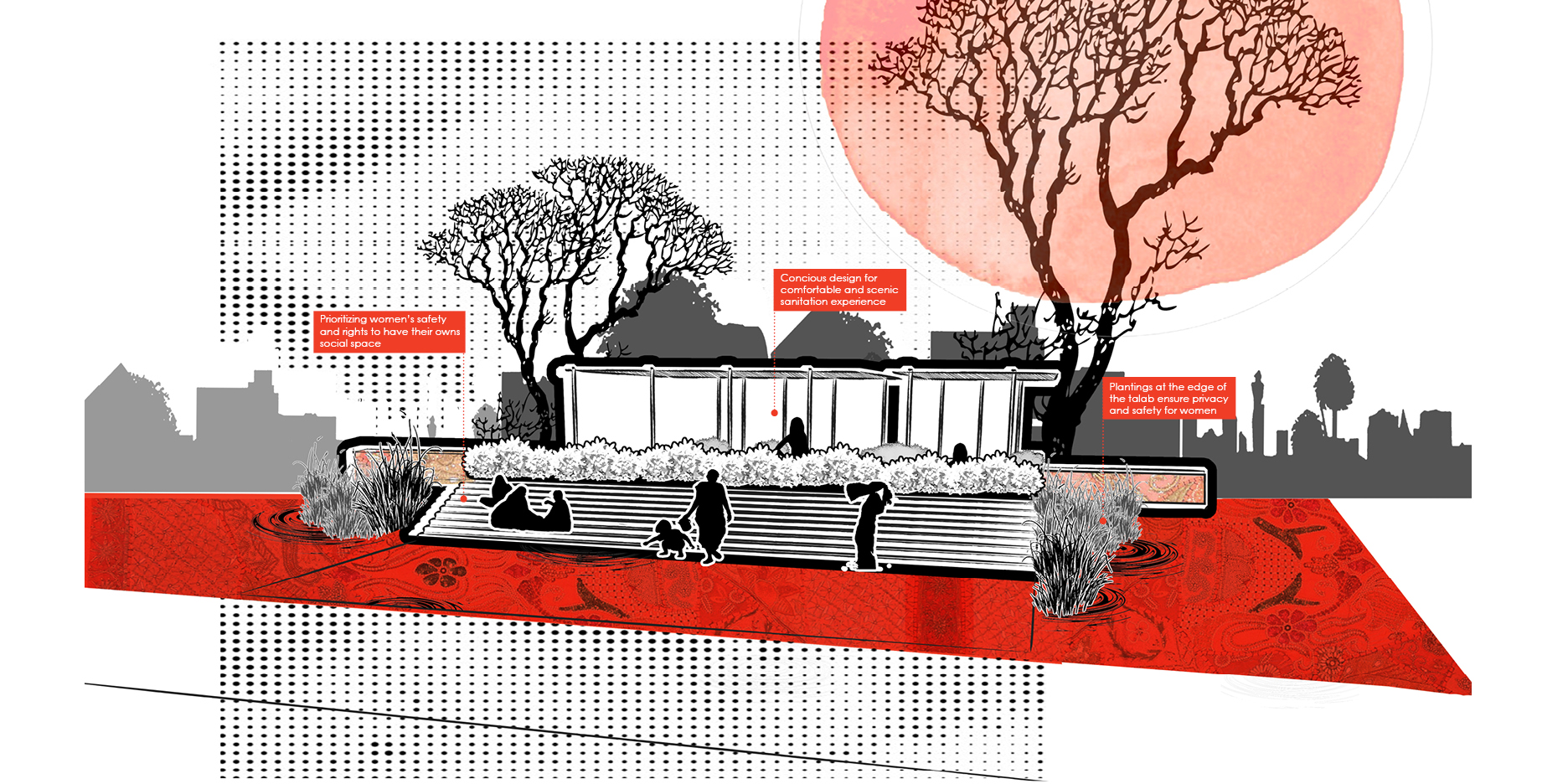

The site plan proposes a redesign of the public realm surrounding the Kho Kho Talab. The site plan features separate women’s and men’s facilities. The women’s facilities include a women-only ghat and garden space that are protected from male intrusion by the water, the planted edge, and the women-only pedestrian walkway. It is integral that women have the right to their own space and safety within the urban landscape.

The sanitation facilities are linked to productive landscapes to yield edible and non-edible crops to support the agricultural industry. The street edge is activated with market spaces and street vendors to sell products produced on and off-site to support the local economy. The historic ghats are restored to honor the sacred cultural practices performed at the site.

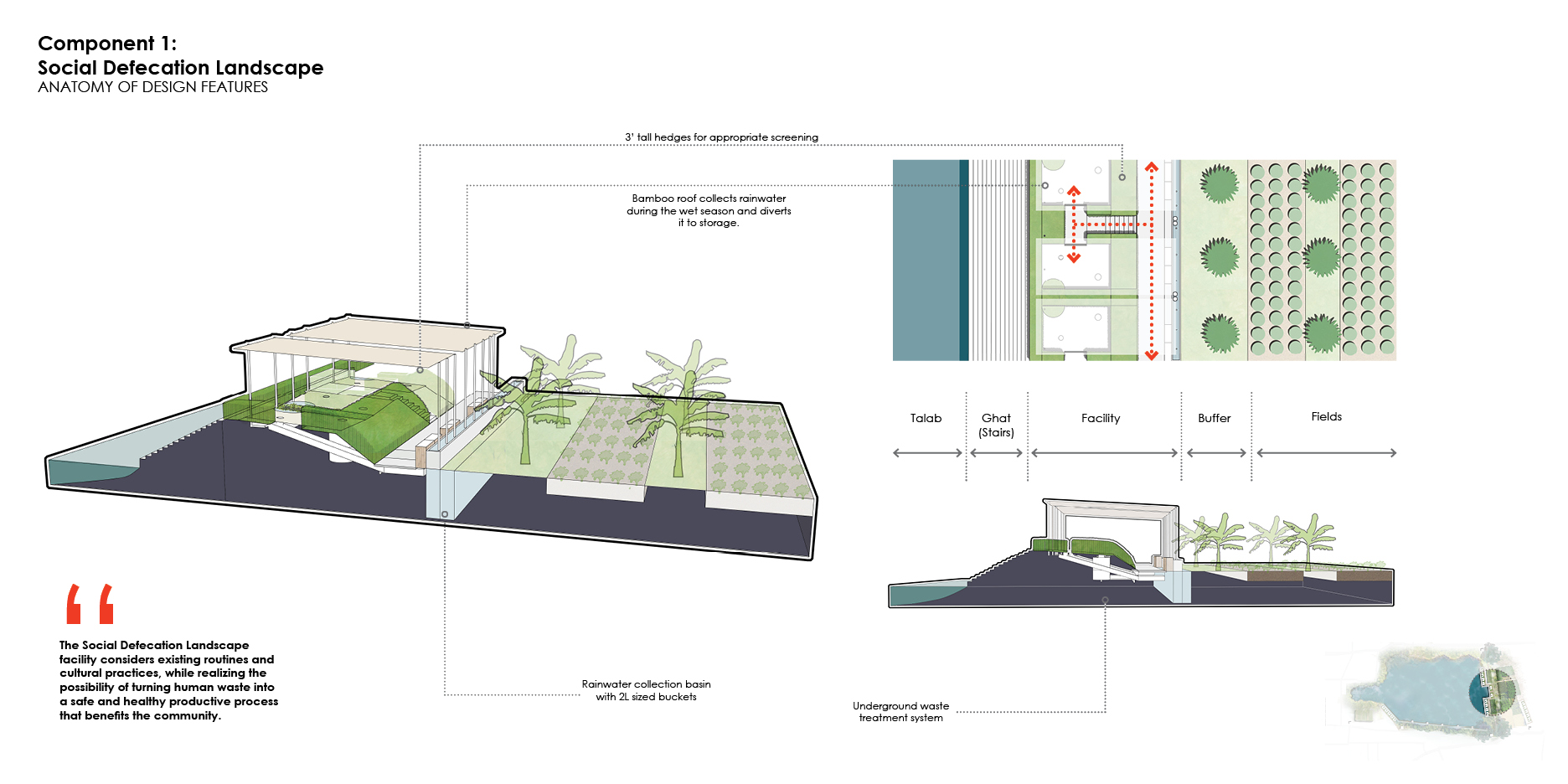

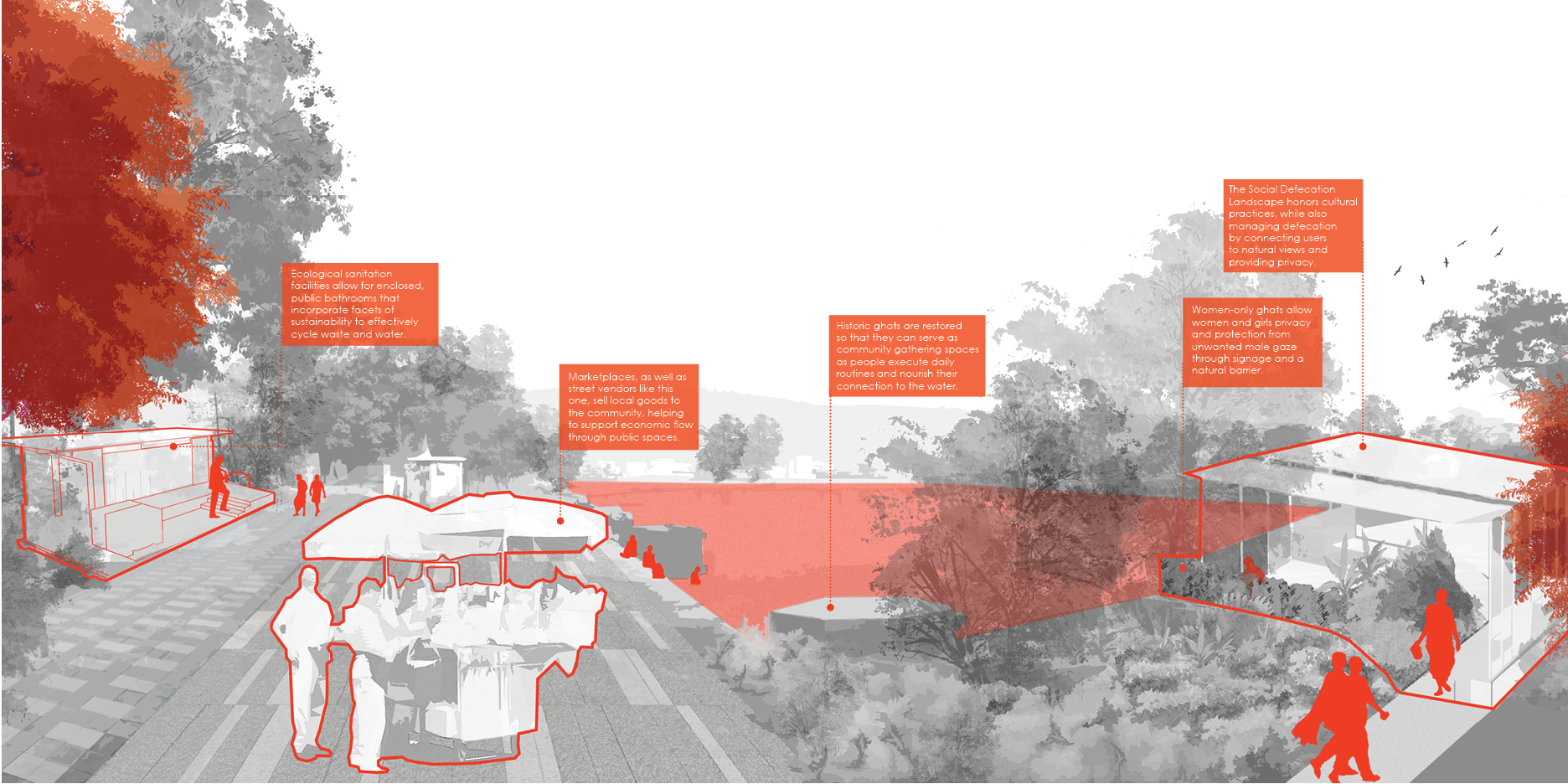

COMPONENT 1: LANDSCAPE-ORIENTED FACILITIES

The landscape-oriented facilities offer some of the perceived benefits of open defecation, such as a visual connection to natural landscapes and squatting actions. While these facilities are designed to draw upon scenic perspectives and plantings to create a pleasant user experience; concealed underground collection and storage support maintenance and cleanliness of the units. Before entering the unit, users collect cleansing water from a hand pump next to the pedestrian walkway. Visitors enter the units from steps that create a staggered height that, along with landscape buffering, ensures privacy within the toilets. The units are comprised of a urinal, latrine, and washbasin.

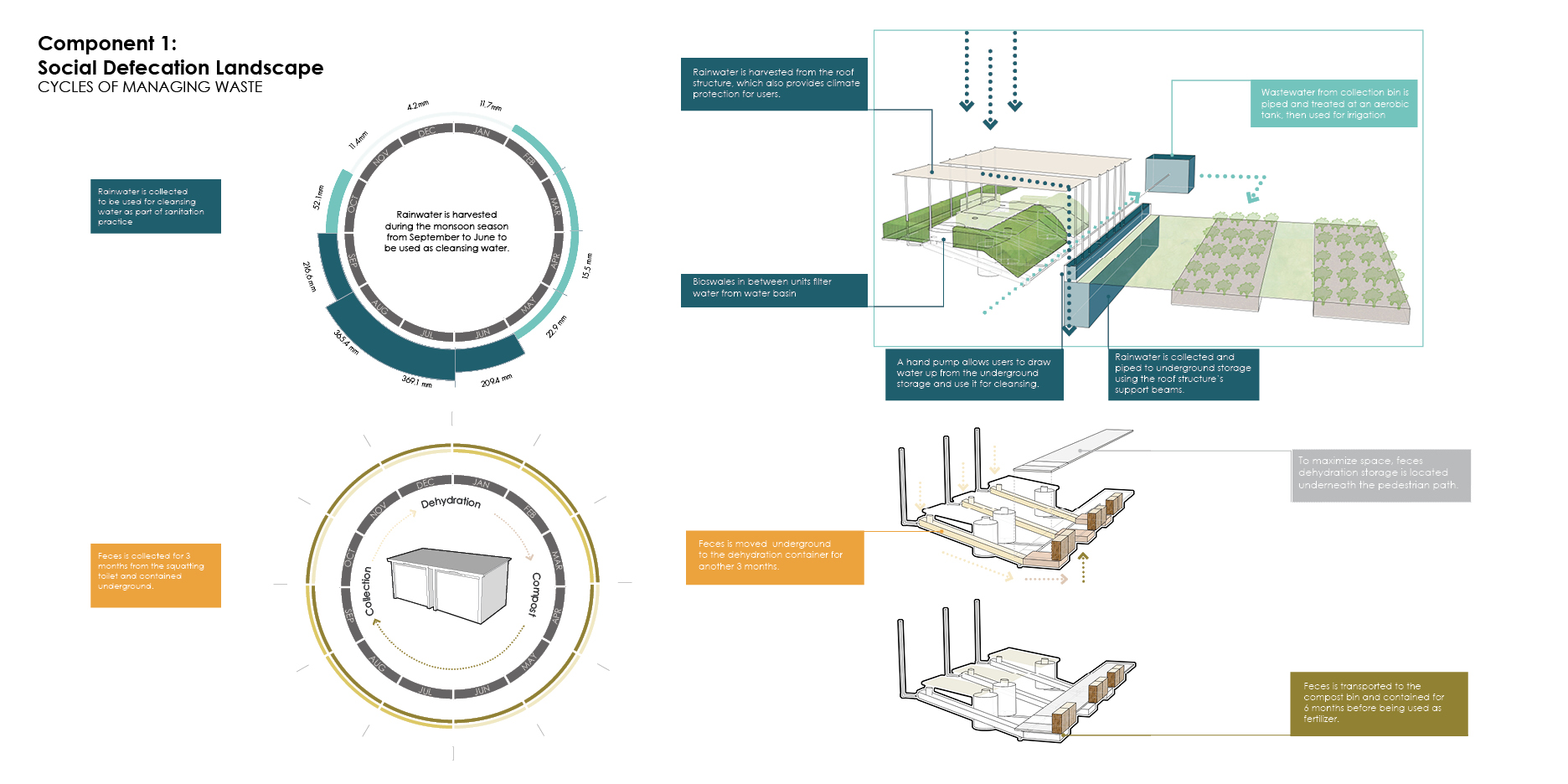

The containment and redirection of water, urine, and fecal matter are vital in managing resources in an effective and sustainable way. Rainwater is collected from the roof and drained through the roof structure support beams to the underground storage. From there, a hand pump lets users draw up the water and use it for cleansing. Liquids drained from fecal collection and urine is moved to be redirected to an aerobic tank for treatment and can later be applied to the productive fields as irrigation. Used water from the washbasin is filtered to a bioswale between toilet units to allow for groundwater recharge.

Fecal matter has more potentially dangerous pathogens, so careful scheduling and limited human intervention are vital in the underground system. Feces is collected for three months by the toilets and contained underground. After the three months have elapsed, the feces is moved to dehydration storage located underneath the pedestrian walkway and remain there for another three months. Both processes will have no human intervention. Following the dehydration process, a removable panel allows the dehydrated feces to be transferred to the compost bins on the other side of the pedestrian walkway and is held for another six months. At the composting step, the dangerous pathogens have been eliminated and the waste is safe to handle. By offsetting the collection-dehydration-composting schedule, all processes can occur simultaneously, and all spaces are utilized.

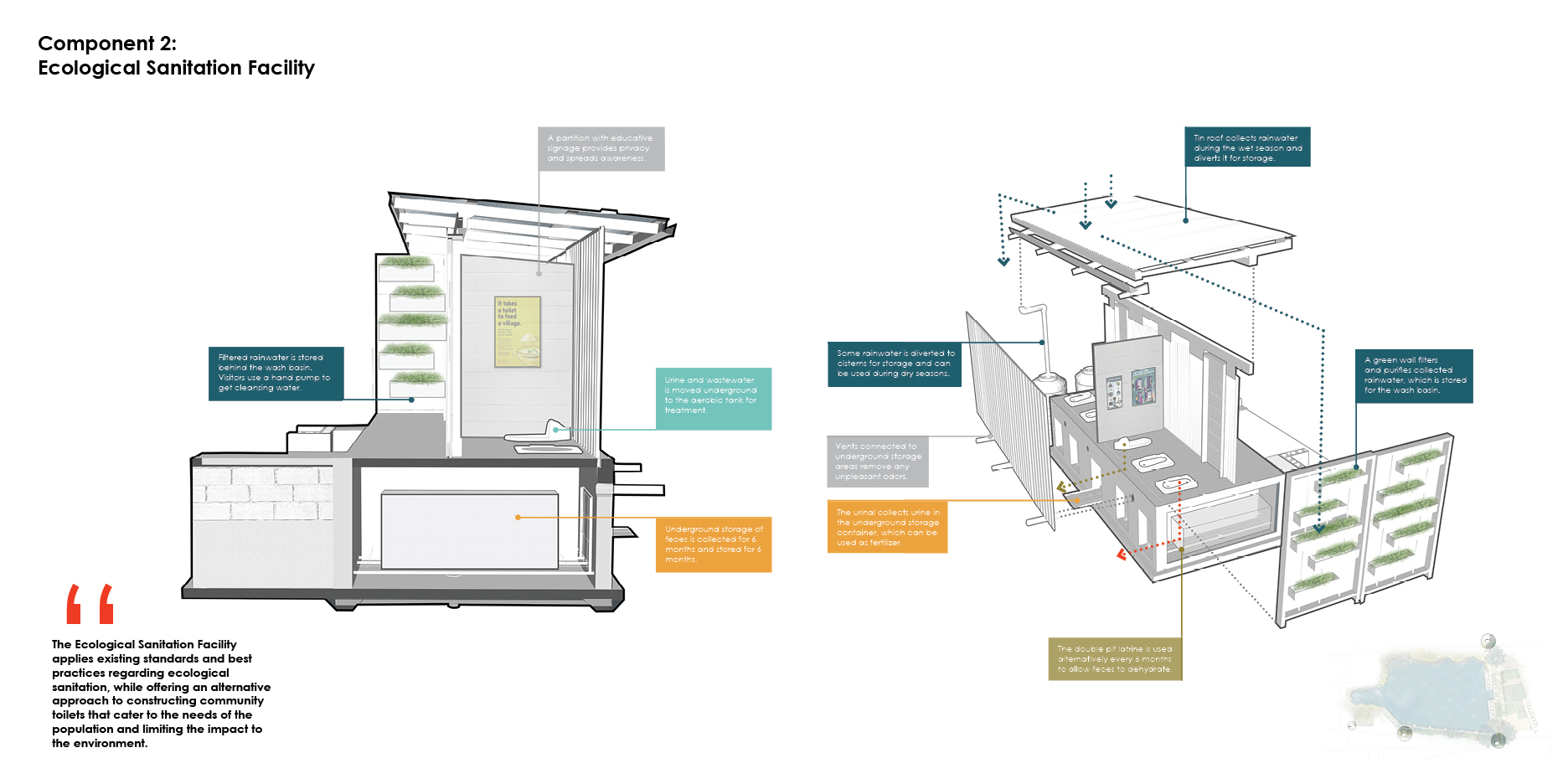

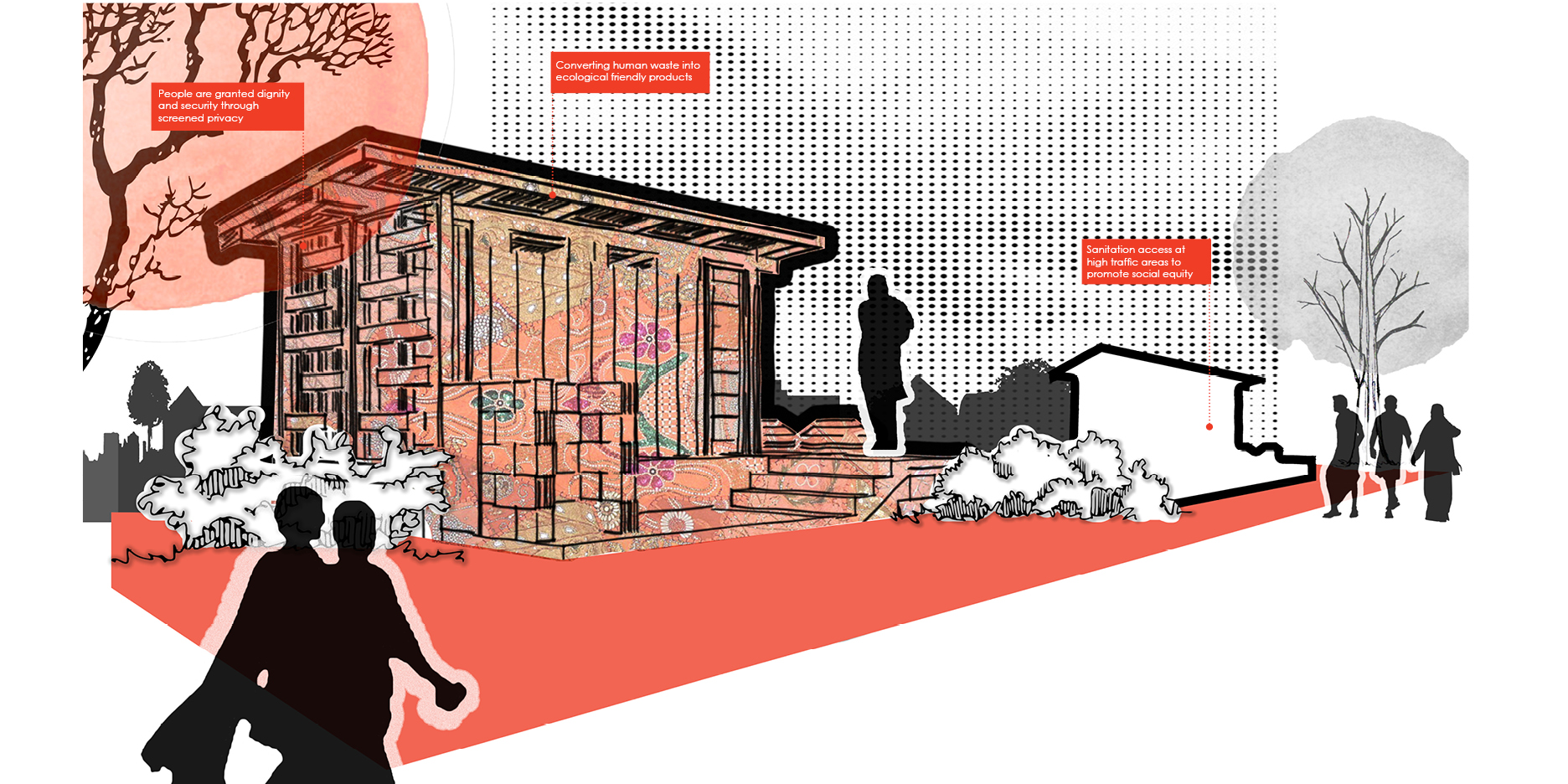

COMPONENT 2: ECOLOGICAL SANITATION FACILITIES

The ecological sanitation facilities present a version of community toilets accessible to people within the public sphere. Similar processes of waste collection and redirection in Component 1 are applied. The roof collects rainwater which is diverted to rainwater cisterns for storage and to a green screen that filters water for the cleansing basin water tank. Feces from the latrine is collected for six months and stored for six months using an alternating latrine method. Urine and wastewater are redirected to an aerobic tank for treatment. A privacy partition between units displays educative signage regarding the threats of open defecation and clarify the processes captured in ecological sanitation facilities.

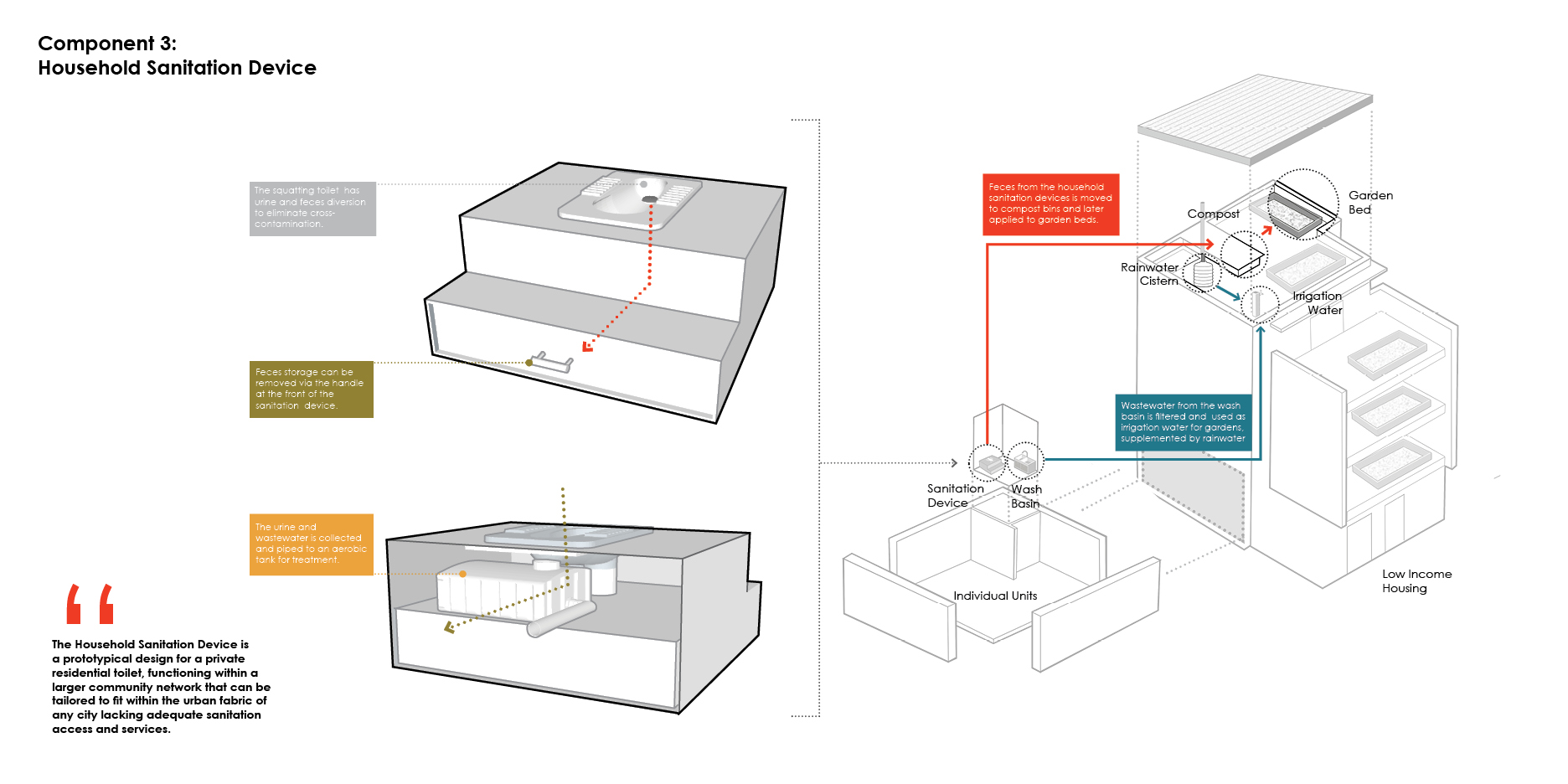

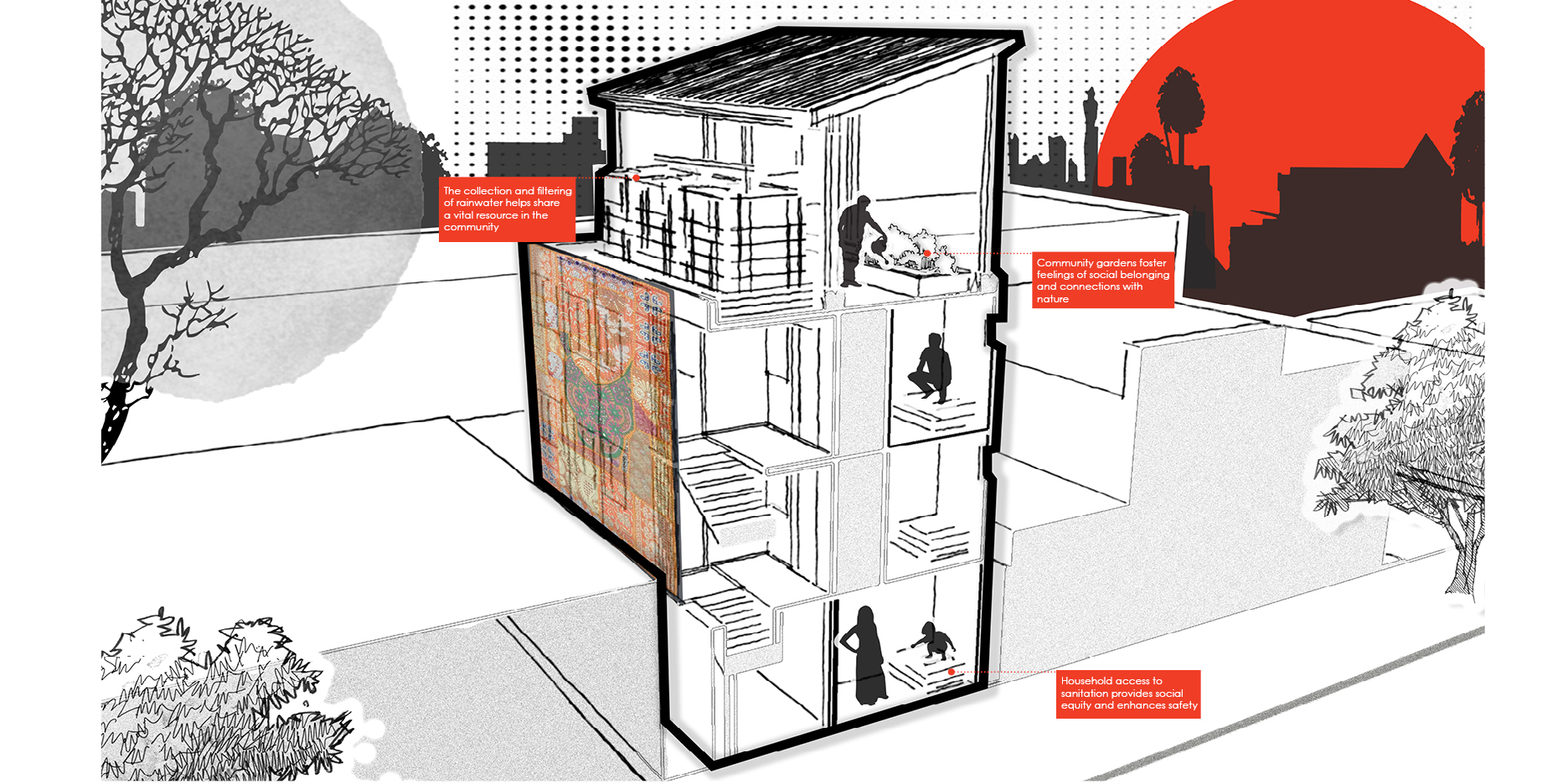

COMPONENT 3: HOUSEHOLD SANITATION DEVICES

The household sanitation device has a removable compartment for feces collection. The urine-diverting toilet directs urine to a pipe for treatment or collected and transported to a drop-off station. The sanitation device is part of a community-scale process. Feces from individual unit devices are contained in community compost bins and can be applied to gardens. Wastewater from sinks, as well as rainwater collected in cisterns, can be used for irrigation. We present a typical design and framework that can be adjusted to meet the needs of specific communities.

TREATING WASTE AT A COMMUNITY SCALE

The design components work together to transform defecation into a productive process that empowers the community rather than endangering it. By activating the voids present in sanitation infrastructure, we are able to create a network of spaces and systems that bridge issues of social equality, women’s rights, wealth disparities, placemaking, and environmental justice to redefine what makes up an inclusive public sphere. In this way, a fundamental human act is translated into a fundamentally human landscape.