Marshcourt

Award of Excellence

Residential Design

Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States

Reed Hilderbrand

A showpiece landscape in Hampshire, England, recalls the height of Britain’s Arts and Crafts movement through a thoughtful restoration and reinvention of work by acclaimed architect Edwin Lutyens with landscape design by Gertrude Jekyll. Troves of documentation and rigorous historical analysis guided the contemporary restoration process and informed floral choices in areas where historic elements had been eliminated, adhering to original stylistic intent while incorporating a more sustainable palette of plants. Restoring the precise geometries of Lutyens’s and Jekyll’s design for an orthogonal set of garden rooms lined with parallel rows required replanting hundreds of yew hedges; away from the house, new interventions in keeping with the historic style extend the site choreography farther afield.

- 2020 Awards Jury

Project Credits

Inskip & Gee Architects, Architecture

Project Statement

Marshcourt is the estate and gardens created by Edwin Lutyens with Gertrude Jekyll in the chalk-veined hills above the River Test in Hampshire, United Kingdom. Constructed between 1901 and 1904, both house and gardens are listed on the National Register of Historic Parks and Gardens — Marshcourt is a quintessential expression of the Arts and Crafts Movement. Lutyens and Jekyll’s design seized particular site conditions in ways bold and subtle to produce an evocative, inventive genius loci. In spring of 2010, the owners of Marshcourt commissioned our practice to develop a master plan for Marshcourt, which, after decades under different owners, lay in decline.

The owners charged us to preserve the landscape while also adapting it to serve as a home for their family. Together we faced the formidable task of stewarding this national treasure into a new era as a contemporary home. This project required different landscape architecture approaches in different places: preservation, renewal or reinterpretation, and, elsewhere, entirely new design that sought, as Lutyens and Jekyll did, to articulate Marshcourt’s extraordinary genius loci.

Project Narrative

While Marshcourt once comprised over 1,300 acres in the early twentieth century, our work addressed the 100 acres surrounding the estate house. Here, many diverse sites and conditions called for a range of approaches, from sensitive renewal to fresh invention.

Our first task was to understand what of the original had been lost and what remained. We turned to historic plans, ordnance surveys and photographs (from the pages of Country Life 1913 and 1932). The decline of the original was evident. Beginning in the 1940s, when Johnson was forced to sell and the property became the home of the Marshcourt Preparatory School, drives were widened, masonry components removed, perennial beds abandoned, and yew hedges either not maintained or removed altogether. Loss continued after the property returned to private ownership in the 1990s, with the flattening of the chalk embankments that structured the drive and the removal of native meadow and woodland to establish expansive lawns for easier maintenance.

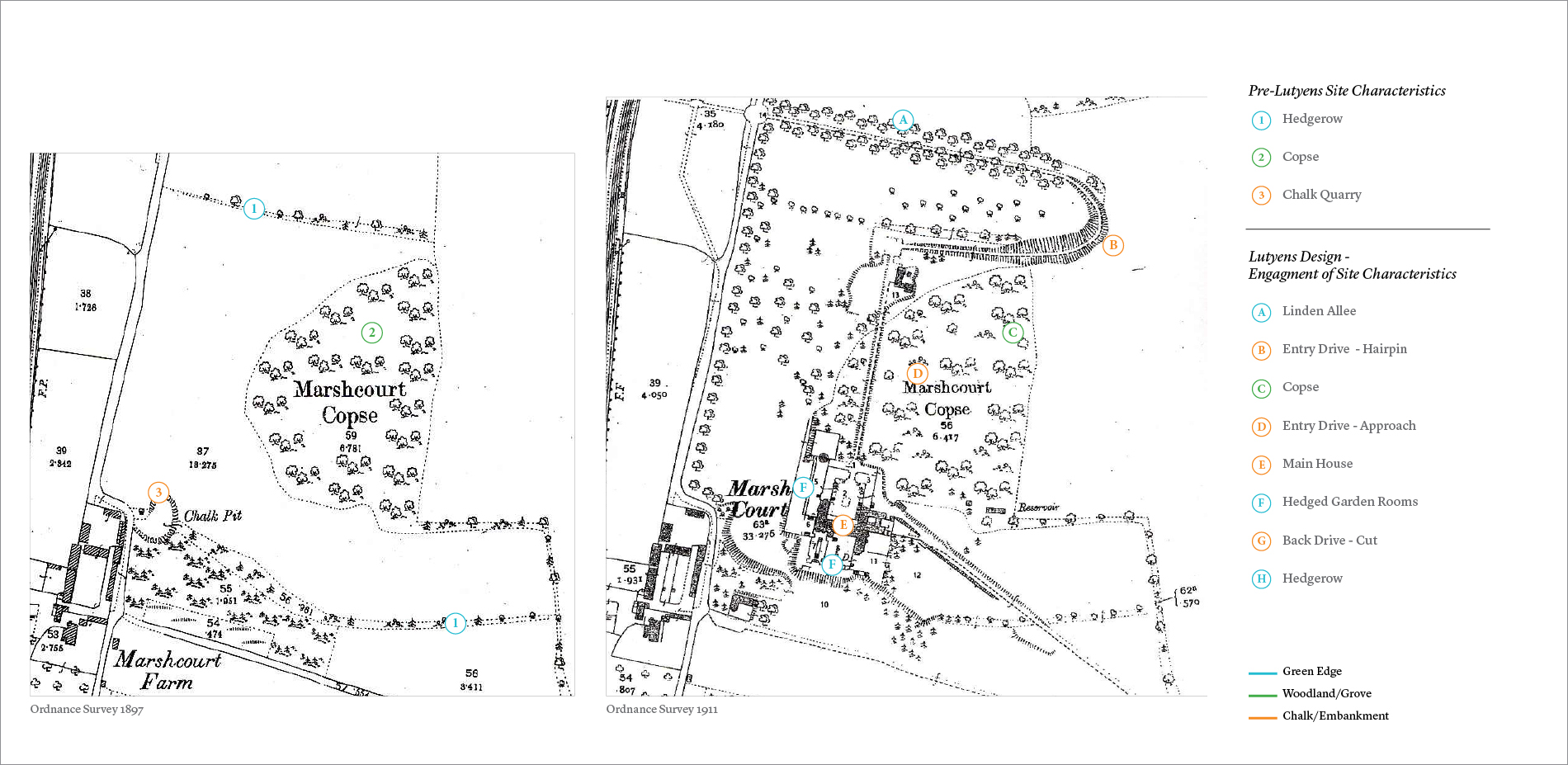

Research into the historic record as well as documentation found on-site revealed what had been lost. But it also illuminated what was unique about the bones of the original design — the relationships Lutyens intended between the site he found and the site he designed. Surveys, which date back to 1897, reveal rural features that existed – an agrarian pattern of fields defined by hedgerows and embankments, the Marshcourt Copse (an ancient woodland) and a chalk pit (a small quarry). A survey of 1912 documents Lutyens’ scheme, specifically the monumental earthwork that shaped a dramatic spatial sequence ascending the hill through deep cuts in the chalk, to then arrive at elaborate terraced gardens that extend from the hillside around the house. Here, Lutyens and Jekyll crafted a series of experiences ranging from enclosed rooms of intensive planting to open platforms with views over the river valley. Above all, the design for the house, gardens, and grounds emphasized the genius loci, a goal which he and Jekyll pursued everywhere they worked.

PRESERVING THE LEGACY

Based on our research and conversation with the client, we established that where we found sufficient evidence to restore the original condition, we would do so. When evidence was insufficient, we would rehabilitate to accommodate new programs appropriate to a home for a large family. Restoration focused, first, on the estate drive and, second, a system of yew hedges enclosing garden rooms at the main house.

CHOREOGRAPHED ARRIVAL

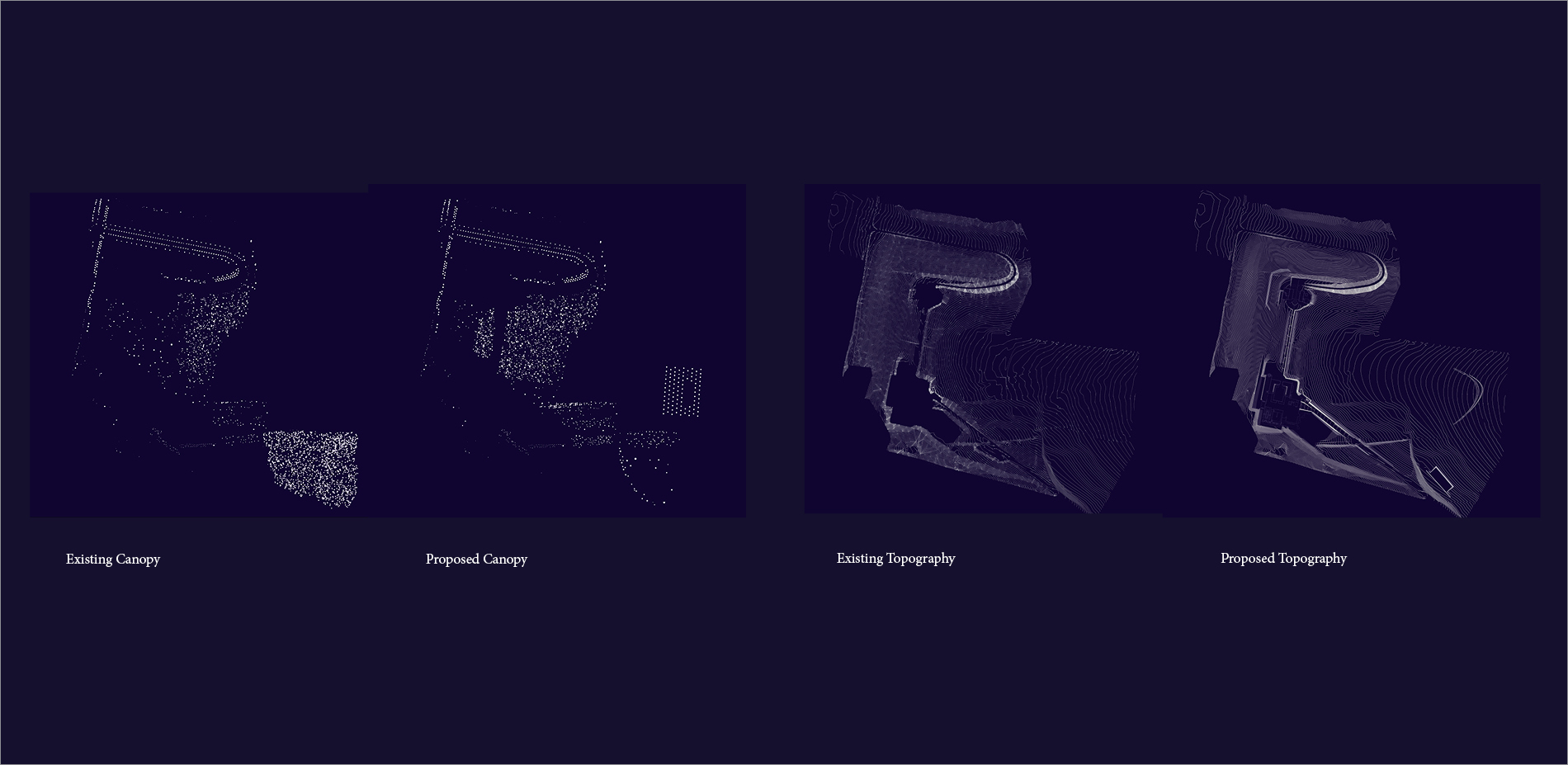

The estate drive is an artery through the entire property that choreographs the unforgettable experience of procession and arrival. Here Lutyens’ fabric had been particularly compromised. Steep, precise embankments on both the front and back drives had been smoothed, understory cleared, meadows replaced with lawn, and hedges removed. Rebuilding the original tectonic relationships we had inferred from the historic record, we proceeded carefully and found geometric relationships and alignments not found in the historic record. Based on these, the drive was re-aligned and narrowed; the square and circular “turning courts” re-figured; the embankments and yew hedges re-instated; an oak canopy and holly, hawthorne, and hornbeam understory replanted; and Marshcourt’s native chalk meadow either allowed to reemerge where extant or seeded where not.

GARDEN ROOMS

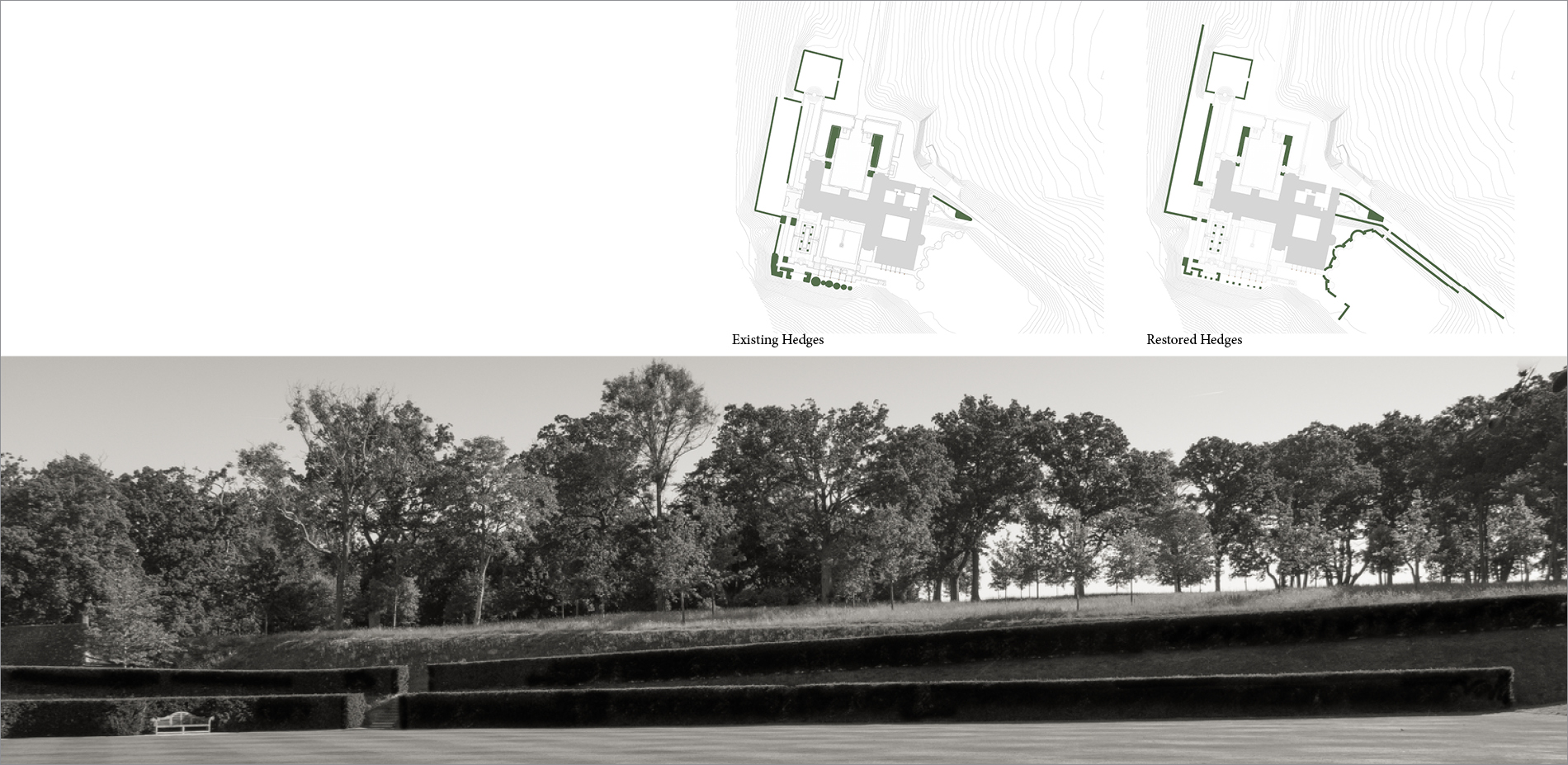

The house itself is a vast white building constructed of chalk with flint, limestone, and brick tile inlay. Its mass rests on an elevated plinth established through dramatic terracing of the hillside. To respond to the steep conditions, Lutyens utilized a rectilinear system of masonry walls and embankments that extend from the house and structure a sequence of garden rooms. The entire masonry architecture of the gardens has been restored. Where masonry wall and balustrades ended, a precisely regulated series of yew hedges completed the geometric figure of the garden rooms.

Much of the hedging had either been removed or had overgrown their intended dimensions by feet. Research had revealed specific intended relationships between the dimensions of the hedging and the articulation of the paving and masonry. For example, centerlines of hedge were set on centerlines of brick pads; tops of hedges were set to align with flint bands of the house or garden walls. To re-establish these intended relationships between hedges and house and garden architecture, we planted hundreds of yews.

AFTER JEKYLL

Although the house and estate design is attributable to Lutyens, archival evidence shows that his long-time collaborator Gertrude Jekyll played a role in the design of the flower gardens around the house. It was early in their partnership. The original planting design for some of the gardens, most clearly documented in historic photographs, appear almost authorless. However, a few demonstrated an approach to plants that exemplified principles espoused by Jekyll: the emphasis on the garden’s ephemeral qualities and seasonal effects through the use of perennials, especially humble cottage garden flowers, familiar roadside natives, and plants from the Mediterranean used in combination with stone.

Historic images revealed the only remaining original plants were two large fig trees. The absence of original planting plans prevented restoration as an option. And while the client was not interested in a historicist recreation of Jekyll’s work, all agreed that the design opportunity lay in giving expression to her beliefs and sensibilities about plants while achieving a more sustainable regime. Our palettes are more restrained than Jekyll’s would have been, but the planting is similarly robust and focused on impressionistic effects to complement the exquisite masonry.

INVENTION

Farther from the house are sites areas that felt physically and experientially disconnected from the original project; Lutyens and Jekyll had not designed them. In these areas we saw opportunities for invention and the promise to complete a choreographed experience of moving from the Test River floodplain past the house and up to the hilltop. Here our interventions ranged from small to large. We used sets of weathering steel stairs that negotiate the steep, tall embankments. To join the historic designed landscape to the outlying fields, we conceived of a 500-foot long, six-foot wide stone path, paved with limestone sets like those in the original entry court, a visual white line in the ground that takes the visitor through oak and hawthorn groves to the high meadow. From here one finds an arcing grass path carved into the grade, leading to a quincunx of 96 European Beech trees around a white precast concrete bench. These Beech canopies one day will unite, forming a shaded woodland.

Just below the beech grove and set into sloping land is a new walled kitchen garden. Within the minimalist handmade brown brick walls that emerge like a sliver out of the land, sit extensive raised beds edged with weathering steel, concrete compost bays with oak gates, stainless steel cables to host espaliered berries, and a greenhouse capped by a potting shed on its east end.

GENIUS LOCI

Deep, visceral ties to the land make Marshcourt a wonderfully special place. Lutyens’ design draws from the geology, and structures an ambitious program using classical and vernacular language in ways both familiar and novel. Clear, precise, and expressive — sometimes quiet, sometimes loud — the historic frame is always read against the painterly effects of shadow and light, the changing seasons, and seventeen different qualities of rain. Here, the Test River Valley and outlying fields are alternately hidden and disclosed, always enticing one to adventure out into the larger English landscape beyond. While Lutyens and Jekyll first envisioned these qualities, we achieved them differently in our own time, according to a plan that interprets an incomplete record, rigorously considers existing conditions, and makes sensitive interventions using a contemporary language of form and material for a family making Marshcourt their home in the 21st century.

Plant List:

- Hawthorn

- Holm Oak

- Silver Birch

- Hornbeam

- English Oak

- Wild Service Tree

- European Beech

- Field Maple

- Dogwood

- Holly

- Whitebeam

- Yew

- Wayfairing Tree

- Guelder Rose

- Wilgenbroek White

- Fig

- White Japanese Wisteria

- Apple Blossom Clematis

- Passionflower

- Colewort