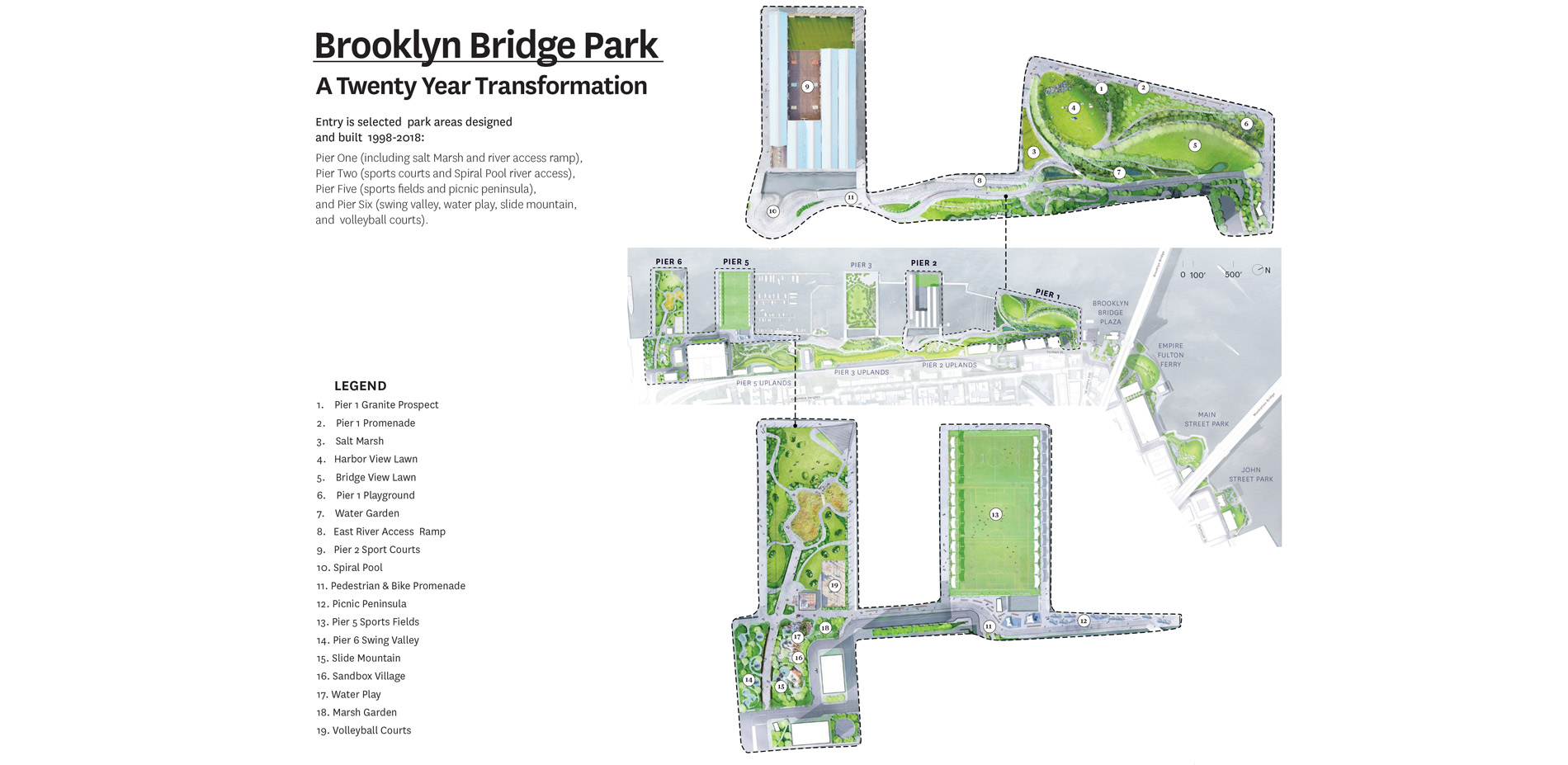

Brooklyn Bridge Park: A Twenty Year Transformation

AWARD OF EXCELLENCE

General Design

Brooklyn, NY, USA | Michael Van Valkenburgh Associates, Inc. | Client: Brooklyn Bridge Park

The plan allows for and encourages different experiences in the different spaces, from being wide open and being fully engaged with the people around you to intimate, forested places. It’s remarkable.

- 2018 Awards Jury

PROJECT CREDITS

- Michael Van Valkenburgh (Landscape Architect)

- Accu-Cost Construction Consultants, Inc. (Cost Estimating)

- AECOM (Civil, Marine, and MEP Engineers)

- Cerami Associates (Acoustical Engineers)

- Domingo Gonzalez Associates, Inc. (Lighting Design)

- Ducibella Venter & Santore (Risk and Protection)

- Eng-Wong Taub & Associates (Transportation Planners)

- Maryann Thompson Architects (Architecture)

- Nitsch Engineering (Stormwater Reuse Consultants)

- Northern Designs (Irrigation)

- OPEN (Graphic Design)

- Paulus, Sokolowski and Sartor (Park Building Architect of Record)

- Pine and Swallow Associates (Soil Scientists)

- Richmond So Engineers, Inc. (Structural Engineers)

- R.J. Van Seters Company (Water Feature Consultants)

- Ysrael A. Seinuk, PC (Structural Engineers)

PROJECT STATEMENT

Last year Brooklyn Bridge Park welcomed 5 million visitors: a mix of locals, far-flung metro area residents, and tourists from around the world. After twenty years of planning and construction, this 83-acre transformation of a post-industrial waterfront is almost complete, but the park has been a fixture in city life since the opening of its first segment in 2010. Having planned this ambitious project to be built incrementally, the designers focused the initial phases on the site's toughest challenges and greatest assets. Adjacent neighborhoods severed from the park site by city infrastructure were reengaged with program-rich urban nodes at existing connection points, while the first pier transformations were optimized for a range of water's edge activities, civic events and active program. Faced with challenging site conditions, the high standards for ecological performance set early in con-struction guided later phases and prompted further innovation. The combination of a locally-focused city edge and a transformative experience of the water cemented Brooklyn Bridge Park as a city park first, but one whose reach continues to grow.

PROJECT NARRATIVE

COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT + INSPIRATION

Brooklyn Bridge Park has been a long time in the making. In 1998, the landscape architects were part of a multidisciplinary team to develop a preliminary economic plan for over a mile of Brooklyn waterfront. Five years later, they were selected by the Brooklyn Bridge Park Development Corporation to be the lead consultant on a master plan, and ultimately to design the park.

There were big questions in the early days of planning: would anybody use a park on a site disconnected from adjacent neighborhoods by a major elevation change and the multi-level Brooklyn-Queens Expressway? What would be the park's relationship to its greatest amenity—the water's edge? And most importantly, what should this park be? How could it appeal to a wide enough range of people to make it thrive, given the known constraints? Over the following years, as they began to answer these questions, the landscape architects participated in some 300 meetings with neighbors and community groups. One Brooklyn Heights resident took the microphone at an early meeting in 1999. "I am elderly and I live on a fixed income," attendees recall her saying. "I can no longer go to the country for vacations. I want to be able to go down to the East River in this park at night, put my toes in the water, and see the reflection of the moon."

Her plea resonated with the designers. The spectacular backdrop of the New York Harbor, East River and Lower Manhattan is irresistible, but they knew scenic value alone would not invite the amount of life needed to sustain the park. The water's edge must be a place to enjoy and use. The design team worked to create as many ways as possible to interact with the shoreline, replacing sheer bulkheads with a complex and varied edge, enabling people to approach and touch the water.

RESILIENCE + INFRASTRUCTURE

The designers also understood that the park must be durable, as the low-lying site faces daily tidal pressures and occasional storm-driven floods of the East River. Synthesizing programmatic and resiliency goals yielded a palette of new edge types that enhance experience while improving environmental performance. Stone riprap banks became an especially versatile tool. Riprap is inexpensive and better than impervious walls at absorbing tides and storm surges, and it can be sculpted into a myriad of usable forms. Lending a material coherence to the entire site, it provides informal seating, steeply graded slopes for boat launches and abrupt elevation changes, sheltered planting pockets, improved marine habitat, and breakwaters for sensitive intertidal ecologies.

The constructed salt marsh at Pier 1 is one of the park's most ambitious shoreline transformations. Realized through intense research and testing with expert consultants, the highly engineered salt marsh returns a once-common ecological community to the urban waterfront and adds a living inter-tidal zone to the park's complement of edge experiences. It has also become an important test case for using larger marshes as flood infrastructure, having readily recovered from the impacts of Hurricane Sandy soon after installation. The accessibility of the tidal environment—particularly the salt marshes—in the heart of the city has made Brooklyn Bridge Park a favorite destination for environmental education programs.

Transforming the industrialized shoreline was a challenge for the designers, but they also found opportunities in the remnant port infrastructure. Extensive structural analysis revealed which of the existing piers were salvageable and what uses they could accommodate. Much of Pier 1 was on fill, rather than structure; this area could support dramatic topographic interventions, including a sloped event lawn sculpted from subway construction spoils, while its more vulnerable pile-supported component was removed and the embankment carved back to create the salt marsh. Piers 2 and 5, both relatively stable, were devoted entirely to turf sports fields and hard courts, optimizing their programmatic potential without overburdening their carrying capacity. Fragments of former warehouses on these piers were repurposed as structures for shelter and lighting.

ACTIVITY + URBAN CONTEXT

The designers focused the first phases of construction on the most critical urban connections: an existing waterfront tourist area next to the Brooklyn Bridge at Old Fulton Street, and the underdeveloped terminus of Atlantic Avenue, an important commercial corridor. Food concessions and ferry terminals at both major entrances tie the park to daily city life and help them function as "urban nodes." Frequent special events at Pier 1's large gathering spaces bring crowds and help build an audience for more everyday uses, including children's play, exercise, sunbathing, and river-viewing from a variety of new elevated prospects. At Pier 6, a 1.6-acre garden-like play space provides a regional attraction while fulfilling a growing need in the neighborhood. A fenced dog run and sand volleyball courts complete the ensemble of programs that transforms this cul-de-sac into a civic hub. Following closely on these threshold landscapes, Piers 2 and 5 were designed to maximize active recreation, satisfying a need in Downtown Brooklyn and bringing users from throughout the city to exercise and play in sublime setting of lower East River. Pier 2's three full size basketball courts, hand-ball courts, play and exercise equipment, roller rink, and multi-use turf field; plus five acres of lined turf fields at Pier 5 have kept these spaces near constant use since their opening, exposing a wider population to the park as a whole. Near a third, neighborhood-scale entry point, New Yorker's from blocks and boroughs away enjoy the city's most picturesque public grilling facility on Pier 5's 40,000-square foot Picnic Peninsula.

CHARACTER + LEGACY

Integrated with intensely programmed areas is a generous mix of landscape experiences, including dense wooded hedgerows, salt and fresh-water wetlands, pastoral shaded greens, and child-size play forests. These living landscapes are shaped by a commitment to responsible use of resources, with species selected for tolerance to urban conditions, salt spray, heavy winds, and periodic saltwater inundation. A large share of the park's irrigation demand is met through reuse of site stormwater. Hedgerow and understory areas are densely planted with small-caliper trees and shrubs, easing establishment and allowing natural succession to determine a well-adapted species composition over time. Since 2010 the designers have worked closely with park gardeners and horticulturalists to maintain and improve the many plant communities as they mature.

With such diversity of programs and landscape types, it was especially important to achieve an overall coherence in the design and to maintain a connection to the rich cultural history of the site. Part of the park's rugged authenticity comes from extensive use of salvaged materials, including stone from a dismantled city bridge for the Granite Prospect at Pier 1 and bench slats made from the aged yellow pine beams of demolished site buildings. New materials and fixtures were chosen for simplicity and durability in an urban coastal environment, inevitably referencing former industrial uses, from galvanized steel and stone riprap common in marine ports to naturally rot-resistant locust fence posts.

Brooklyn Bridge Park is a success because its designers embraced the realities of the site when they envisioned what the park could become. The constructed ecologies are not designed as pure nature, but part of an urban experience, and for this reason they thrive in the heart of a populous city. Hundreds of New Yorkers can gather for a summer film festival while a delicately calibrated salt marsh community grows only a few feet away. The provision of things for people to do, not just things to see, has helped form a loyal local constituency and regular users from throughout the city and beyond, ensuring that the park has the broad base of support it needs to be an enduring cultural institution.