Bryant Park

New York City USA

OLIN, Philadelphia USA

Client: Bryant Park Corporation

Close Me!

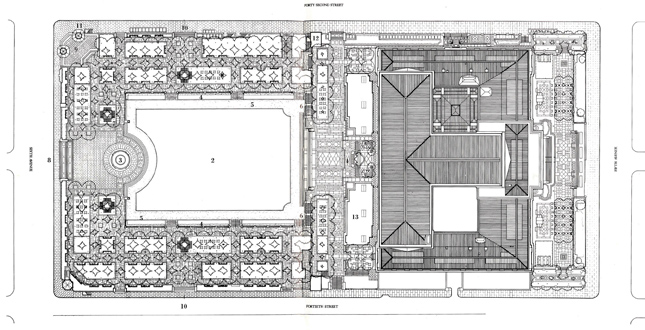

Close Me!Site Plan

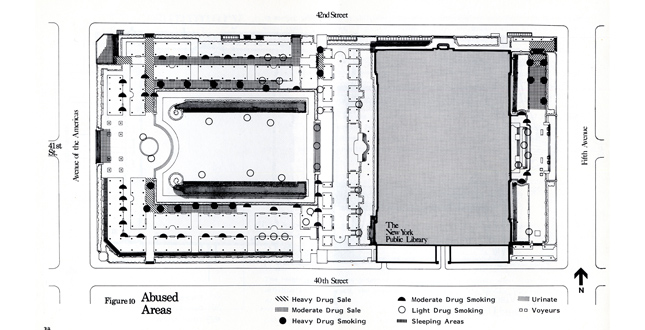

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Bryant Park: Intimidation or Recreation? 1981, by Project for Public Spaces, Inc.

Photo 1 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!A portion of the field study documenting social problems in Bryant Park in 1981

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: OLIN

Photo 2 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Bryant Park before the redesign: difficult access, overgrown, dark and foreboding.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: OLIN

Photo 3 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Construction sequence: excavation for library stacks; filling the hole with miles of shelving; putting the lawn back and the park together.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: OLIN

Photo 4 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Opening up the park with new stairs and new castings of Larreré and Hastings ornamental torchères.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: OLIN

Photo 5 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Preservation of the groves of plane trees with the expanded lawn.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Peter Mauss/Esto

Photo 6 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!(1993) Shortly after the redesign, Bryant Park became a destination for visitors and residents.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Felice Frankel

Photo 7 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!One of the several new garden kiosks provides food and beverages for the convenience and pleasure of visitors and to insure use and safety within the park.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Peter Mauss/Esto

Photo 8 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Connectivity and free movement between the levels and parts of the park provided safety and convenience.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Peter Mauss/Esto

Photo 9 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!Refurbished bosques with recycled stone pavement and, at the time (1982), an innovative use of chairs for social flexibility.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Peter Mauss/Esto

Photo 10 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!One of several relocated historic statues and revival of historic use of gravel in lieu of paved surfaces.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Peter Mauss/Esto

Photo 11 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!One of two exuberant 300-foot herbaceous planters that frame the lawn and provide seasonal change and interest.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Peter Mauss/Esto

Photo 12 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!A place to escape from the city at its very heart — the restored Lowell fountain in the background.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Felice Frankel

Photo 13 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!A place to come together for events and programmed activities such as free movies in summer.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Peter Mauss/Esto

Photo 14 of 15

Close Me!

Close Me!A social success, due to programming and management, and its physical design—a few elements carefully selected and well made.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: Peter Mauss/Esto

Photo 15 of 15

Project Statement

As a high-profile and cherished public space in one of the world's most important urban centers, the enormously successful restoration of Bryant Park was pivotal for New York City and serves as the definitive model of urban park restoration and environmental, social and economic sustainability.

Project Narrative

—2010 Professional Awards Jury

"Thousands of people cooped up in rooms and corridors need a place where they can change their depth of focus and be in nature while in the heart of the city." (Quote from the landscape architect who led the design of Bryant Park's restoration)

As a high-profile and cherished public space in one of the world's most important urban centers, the enormously successful restoration of Bryant Park was pivotal for New York City and serves as the definitive model of urban park restoration and environmental, social and economic sustainability.

Bryant Park, directly adjacent to the New York Public Library, began to deteriorate in the early 1900s due to poor design and lack of maintenance. Despite redesign and a revival in the 1930s and 40s, conditions steadily worsened, and by the 1960s the park was replete with illegal activity. In 1966, The New York Times referred to it as a magnet for "addicts, prostitutes, winos and derelicts." By the early 1970s, police barricades became necessary at all of the park's entrances after 9:00 PM.

The future of Bryant Park took a positive turn in 1979 when the New York Public Library began plans for an extensive building renovation that included addressing the problems of Bryant Park, the Library's backyard. Urban planner and sociologist William H. Whyte, a pioneer in research exploring design's influence on human behavior, was commissioned to analyze why the park was a sanctuary for criminals and to recommend viable solutions. It was determined that many of the social problems were a direct result of the park's historic design. He suggested simple yet effective changes to the site, such as removing iron fences and shrubbery to make the space more physically and visually accessible. "Access is the nub of the solution," wrote Whyte. Using Whyte's report as a guide, the landscape architect was hired in 1986 to create a design that would transform Bryant Park into a safe and vibrant urban nexus. The project was a landmark experiment in design and social programming created in response to sociology and behavioral research.

The design included numerous small changes that would yield significant results. The landscape architect modified and added entrances, ramps, stairs, and pavements while cutting through walks and railing to configure free circulation. The design also included concessions, public restrooms, and entertainment programming as critical components of a successful restoration. During the design process, stone paving from the 1934 scheme was salvaged for reuse and gravel walks were introduced at the heart of the park. The derelict hedges in the central area that had proved to be a serious maintenance and safety problem were removed. The lawn was enlarged and two 300-foot-long borders containing herbaceous perennials and evergreens were placed against the walls and railings where they could be seen and enjoyed without forming a physical or visual barrier. The landscape architect's research discovered two cast iron lamp designs conceived by the architecture firm of John M. Carrere and Thomas Hastings for the New York Public Library and the terraces that accompanied it. Working with a foundry in New Jersey, additional new cast iron ornamental torchères were made for the new openings into the park and its redesigned rear terrace where a major through-block crossing was created. The historic fountain by Charles Adam Platt was completely rebuilt with new mechanical equipment. The surrounding streets—40th, 6th Avenue and 42nd Street—were relit with new castings of the Olmsted Bishop's Crook lamp and the cast iron railings on the perimeter walls were adjusted and restored. The restoration's long-term environmental sustainability was insured by the landscape architect's commitment to incorporating durable and natural materials throughout the park.

Many visitors to Bryant Park are unaware that the site is a large-scale green roof—a landmark of environmental sustainability. During the design of the restoration, the New York Public Library announced additional book stacks were needed. The landscape architect, an innovator in the design of landscape over structure since the 1970s, logically suggested submerging the stacks beneath the Park. The two-story stack extension is connected to the library by a 62-foot-long tunnel and houses over three million volumes. Smoke purge vents are concealed within the floral borders and a fire escape is beneath a dedicatory plaque.

The social environment of Bryant Park was transformed within days of the restoration's completion in April 1992. In an article published in May 1992, The New York Times cited, "Where once the park was the home of derelicts, drug dealers and drug users, it is now awash with office workers, shoppers, strollers and readers from the New York Public Library next door."

Over 15 years later, Bryant Park draws thousands of visitors every day and is a landmark of social sustainability. The park is active year-round with concerts, performances, movie screenings, and ice skating. Some critics argue the park is overly programmed, however, this revenue has assured superb maintenance and care for the park and its continued sustainability—environmentally, economically, and socially—inspiring others across the United States and abroad.

Economic sustainability is a hallmark of Bryant Park. The restoration of the park marked the beginning of an era where public/private partnerships became the financiers and guardians of the public realm—a watershed moment in the history of park making. Today, Bryant Park is managed by a not-for-profit, private company, originally formed to raise private funds for the restoration of the park. The company is responsible for maintenance of the space, which is financed entirely by private funds with a large portion coming from local merchants, property owners, neighbors and citizens. It is the largest organization in the nation to manage a public park with private funding.

In addition, Bryant Park demonstrates the direct correlation between open space and land value. After the restoration, building leases and land values of properties near the park increased dramatically. As a result, developers and land planners now understand that positively charged, socially viable open space lends significant value to development in the urban realm.

Project Resources

Lead Designer

OLIN

Laurie Olin, FASLA

Architects

Davis Brody Bond LLP, library stacks architect

Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates, kiosks/cafés architect

Mechanical and Electrical Engineer

AltieriSeborWieber LLC.

Lighting Design

Brandston Partnership, Inc.

Mechanical and Electrical Engineer Plumbing Engineer

Joseph R. Loring & Associates, Inc.

Design of Perennial Beds and Horticulture

Lynden B. Miller Garden Design

Structural Engineer

Rosenwasser/Grossman Consulting Engineers, PC

Construction Management

Tishman Construction Corporation