Honor Award

The High Line, Section 1

New York City USA

James Corner Field Operations (project lead) and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, New York City USA

Client: The City of New York / Friends of the High Line

Close Me!

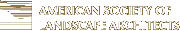

Close Me!Section 1 of the High Line extends over nine city blocks from Gansevoort Street to West 20th Street on the west side of Manhattan.

Photo: This map was produced by Friends of the High Line. All images created by James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Courtesy the City of New York. Map design: Patrick Hazari. First edition © 2009 Friends of the High Line.

Photo 1 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!View of the Gansevoort entry, looking north. The existing cut at the southern terminus is restored and treated to expose the layered construction and infrastructure of the landscape above.

Photo: © James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Courtesy the City of New York

Photo 2 of 16

Close Me!

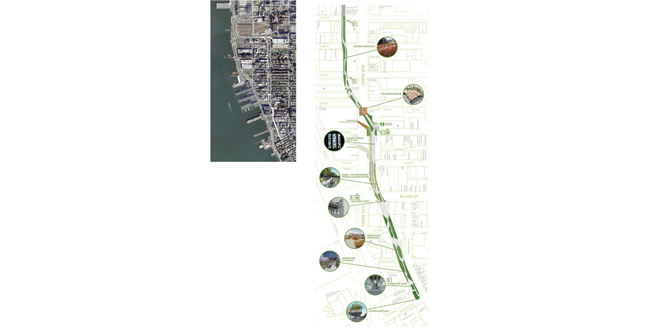

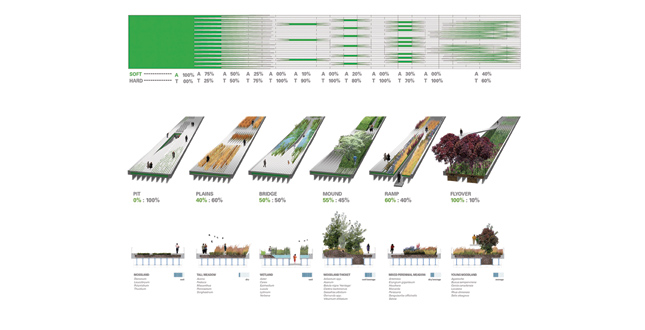

Close Me!The invention of a new paving system allows for meandering movement along the High Line while maintaining minimum path widths. Plant types are easily reconfigured to construct hard surfaces that are materially consistent and spatially variable.

Photo: © James Corner Field Operations

Photo 3 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!By changing the rules of engagement between plant life and pedestrians, the strategy of "agri-tecture" combines organic and building materials into a blend of changing proportions from high-use areas (100 percent hard) to richly vegetated biotopes (100 percent soft).

Photo: © James Corner Field Operations and Diller Scofidio + Renfro, Courtesy the City of New York

Photo 4 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!A modular system of precast concrete planks with open joints and specially tapered edges and seams permits the free flow of water (collected for irrigation) and directs water into planting beds.

Photo: © James Corner Field Operations

Photo 5 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!Aerial nighttime view, looking south. The project establishes an urban corridor for habitat, wildlife, and people, and provides opportunity for future links between greenways and parkways along the Hudson River.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Photo 6 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The High Line landscape is marked by slowness, distraction and an otherworldliness that preserves the strange, wild character of the High Line, yet doesn't underestimate its intended use and popularity as a new public space.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Photo 7 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The Washington Grasslands, looking south. An integrated system incorporates drainage, utilities and existing rail tracks and switches with new paving, planting, lighting and seating.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Photo 8 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The Gansevoort Woodland, looking south. The park is designed as a slow space for walking and contemplation, reinforced through the sensitive choreography of pathways responsive to found conditions, views of the city and river beyond and intimate rooms within.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Photo 9 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!Aerial view of the Tenth Avenue Square. Wood seating steps cut into the existing structure with views up Tenth Avenue while a wooden deck with trees and seating is oriented toward views of the Statue of Liberty.

Photo: © Barrett Doherty

Photo 10 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The Tenth Avenue Square, with amphitheater-like seating and an unusual view up Tenth Avenue at 17th Street.

Download Hi-Res ImagePhoto: © Iwan Baan

Photo 11 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The Sundeck, one of the High Line's most popular gathering spots, between West 14th and West 15th Streets. Large-scale outdoor furnishing, aligned along a gentle curve of historic rail track, is surrounded by fragrant grasses and perennials.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Photo 12 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The Chelsea Grasslands, looking north. New plant species were carefully selected to produce a primarily native, resilient, and low-maintenance landscape, building upon the existing self-sown landscape and working with specific environmental conditions and microclimates.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Photo 13 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The Washington Grasslands, looking south. A flock of peel-up benches are arranged to encourage social seating. Lighting is installed below eye level illuminating the pathways for safety, while allowing the eye to appreciate the city beyond and the nighttime sky.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Photo 14 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The Chelsea Market Tunnel, looking south. Combinations of white and blue LED fixtures create a dramatic space at night overlooking the Hudson River. The tunnel also showcases a variety of public artists through extensive art programming and rotating exhibitions.

Photo: © Iwan Baan

Photo 15 of 16

Close Me!

Close Me!The Chelsea Grasslands in the fall, looking south. A dominant grassland matrix provides consistency, with punctuated and theatrical blooms of perennials, trees, and shrubs for diversity, seasonal interest, texture, fragrance, and height and color variation.

Photo: © Barrett Doherty

Photo 16 of 16

Project Statement

The High Line is a precedent urban park that reclaims a former elevated railroad for new use, promoting timely principles of ecological sustainability, urban regeneration and adaptive reuse. Preservation and innovation come together to establish an urban corridor for habitat, wildlife and people. In addition to providing valuable open space for New York City, the High Line has become an economic generator for the neighborhood, attracting investment toward new cultural institutions, commercial and residential development.

Project Narrative

—2010 Professional Awards Jury

Site and Context

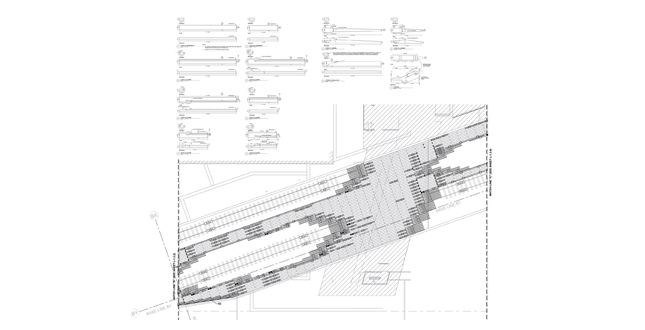

The first section of the High Line is 2.88 acres and over 0.5 miles long. It extends over nine city blocks from Gansevoort Street to West 20th Street, crossing through the Historic Meat Packing District and West Chelsea neighborhoods. Built in the 1930s as part of the West Side Improvement Project, the High Line lifted freight traffic 30 feet in the air, removing dangerous trains from the streets below. Since the last train ran in 1980, the line was left unused for 25 years and was considered an eyesore in disrepair, a blight to the neighborhood and was subsequently under threat of demolition. During that time a thin layer of soil formed and an opportunistic landscape of early successional species began to grow, capturing the imagination of a few New Yorkers and triggering the idea for its conversion into a park. In 1999, the Friends of the High Line formed with the mission to save the High Line and transform it into an extraordinary public park.

The landscape architect was hired by the City of New York and the Friends of the High Line to lead a collaborative team of over 15 specialists to design the first two sections of the line and provide a framework plan for the entire 1.45 miles including developer coordination to encourage positive relationships between the park and its adjacencies. The scope challenged designers to retrofit the existing structure (making it safe, accessible and usable), to retain elements of the historic railroad and abandoned High Line landscape, and to give the High Line a compelling new life and future as a one-of-a-kind recreational amenity and public promenade.

Major constraints included extreme conditions associated with an elevated structure, such as its exposure to wind and cold from above and below; minimal width (30–50 feet) and depth (18–24 inches); difficulty of providing public access via new stairs and elevators over privately owned properties; installation and implementation issues associated with an elevated structure (18–30 feet high) that crosses over 22 public streets through dense neighborhoods; ownership issues related to existing and potential private developers underneath and adjacent to the structure; and upgrades and repair of the existing structure to meet code and health and safety regulations.

This type of project—to transform an elevated rail structure into a new public park—was unprecedented in the United States, and as such, the design had to be especially innovative and creative in its physicality, promotion of green materials and practices, phased implementation, short-term and long-term planning and consideration of future maintenance and operations.

Design

Inspired by the melancholic, "found" beauty of the High Line, where nature has reclaimed a once-vital piece of urban infrastructure, the design aims to refit this industrial conveyance into a postindustrial instrument of leisure. By changing the rules of engagement between plant life and pedestrians, our strategy of "agri-tecture" combines organic and building materials into a blend of changing proportions that accommodates the wild, the cultivated, the intimate, and the social. In stark contrast to the speed of Hudson River Park, the singular linear experience of the new High Line landscape is marked by slowness, distraction and an otherworldliness that preserves the strange, wild character of the High Line, yet doesn't underestimate its intended use and popularity as a new public space. This notion underpins the overall strategy—the invention of a new paving and planting system that allows for varying ratios of hard to soft surface that transition from high-use areas (100 percent hard) to richly vegetated biotopes (100 percent soft), with a variety of experiential gradients in between.

Our position has always been to try and respect the character of the High Line itself and not destroy the very properties that made it such a magical phenomenon in the first place: its singularity and linearity, its straightforward pragmatism, its scale, both intimate and immense at the same time, and its emergent properties with wild plant-life—meadows, thickets, vines, mosses, flowers—intermixed with ballast, steel and concrete. Our solution is primarily threefold: first the invention of a new paving system, built from linear concrete planks with open joints, specially tapered edges and seams that permit the free flow of water (collected for irrigation) and the intermingling of organic plant-life with harder materials. Less a pathway and more a combed or furrowed landscape surface, this intermixing of plants with paving creates a rambling, textural effect of immersion, strolling "within" and "amongst" rather than feeling distanced from. The selection and arrangement of grasses and plants further helps to define a wild, dynamic character, distinct from a typical manicured landscape, and representative of the extreme conditions and shallow rooting depth. The second strategy is to slow things down, to promote a sense of duration and of being in another place, where time seems less pressing. Long stairways, meandering pathways, and hidden niches encourage taking one's time. The third approach involves a careful sense of dimension and scale, minimizing the current tendency to make things bigger and obvious, seeking instead a more subtle gauge of the High Line's measure. This blend of old with new, of organic with inorganic, of close-up with distant, and of landscape with urbanism provide an episodic and varied sequence of public spaces and landscapes set along a simple and consistent line—a line that cuts across some of the most remarkable elevated vistas of Manhattan and the Hudson River.

As an ambitious urban reclamation project, the High Line's very essence is born out of the desire to preserve and recycle. Section 1 transforms 2,640 linear feet of infrastructure into parkland, reducing the heat island effect and providing habitat for animals, insects and birds. All lead paint was stripped from the structure and all hazardous materials removed from the site. Two hundred and ten species of perennials, grasses, shrubs and trees were carefully selected to produce a primarily native, resilient, and low-maintenance landscape, building upon the existing self-sown landscape and working with specific environmental conditions and microclimates. A dominant grassland matrix provides consistency, with punctuated and theatrical blooms of perennials, trees and shrubs for diversity, seasonal interest, texture, fragrance, and height and color variation. Green roof systems and technologies enhance water retention, drainage and aeration and minimize irrigation requirements. This in combination with open joint pavement ensure that over 80 percent of the water that falls on the High Line stays on the High Line. Energy-efficient LED lighting is installed below eye level illuminating the pathways for safety, while allowing the eye to appreciate the city beyond and the nighttime sky.

As a public–private partnership, the realization of the High Line underwent intense community participation in the form of workshops and presentations throughout the design process, intricate agency coordination with federal, state and city agencies, and private donor engagement to fund special features and establish an endowment for the maintenance and operations of the park. Since its opening, the High Line has received praise and acclaim and has been well used and loved by local residents, tourists, design critics and even the most cynical of New Yorkers. In addition to providing much-needed open space in New York and reintroducing the notion of 'promenading' back into the urban park experience, the High Line's long-term economical and ecological goals have made a significant contribution to the discipline of landscape architecture and the advancement of economic, ecological and sustainable design.

Project Resources

Design Team

James Corner Field Operations (Project Lead)

James Corner, ASLA

Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Consultants

Buro Happold, Structural / MEP Engineering

Robert Silman Associates, Structural Engineering/ Historic Preservation

Piet Oudolf, Planting

L’Observatoire International, Lighting

Pentagram Design, Inc, Signage

Northern Designs, Irrigation

GRB Services, Inc., Environmental Engineering / Site Remediation

Philip Habib & Associates, Civil & Traffic Engineering

Pine & Swallow Associates, Inc., Soil Science

ETM Associates, Public Space Management

CMS Collaborative, Water Feature Engineering

VJ Associates, Cost Estimating

Code Consultants Professional Engineers, Code Consulting

Control Point Associates, Inc., Surveying

Municipal Expediting Inc., Expediting

Paul DiBona Specifications LLC, Technical Specifications

Construction Team

LiRo/Daniel Frankfurt, Resident Engineer

SiteWorks Landscape, Construction Management

Helen Neuhaus & Associates, Community Liaison

KiSKA Construction, General Contractor

Bovis Lend Lease, Construction Management